Jordanes

GETICA

siveDe Origine Actibusque Gothorum

with “classicized” grammar, normalized spelling and some emendations

by

Þeedrich Yeat

| Romana ⇐ (Complete) |

First Half | Getica Second half ⇒ |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

Although Jordanes tells us (# 266) that he is of Gothic descent and may indeed be partly or even fully a Goth, his name itself is not Germanic. He explains toward the end of chapter 49 that his grandfather was called Farja and his father Wiha-moð, both Gothic names, and that his grandfather had been secretary to the Alan leader Candac and he himself secretary to the Ostrogothic chieftain Gunþi-gis before his “conversion” (perhaps from Arianism to Catholicism). The name of one Jordanes Crotonensis, bishop of Crotona (now Cotrone) in Bruttium (southern Italy) is found, with those of several other bishops, appended to a document sometimes called the Damnatio Theodori, issued by pope Vigilius in August 551 at Constantinople. Jordanes’ history of the Goths (also called the Getica ) includes in part a summation of a 12-volume history by Senator Cassiodorus, “On the Origin and Deeds of the Goths from Long Ago and Descending through Generations and Kings to Now.” Even if not a bishop, Jordanes was at least a monk or similar ecclesiastic, and wrote his own work in Constantinople in A.D. 551 under Emperor Justinian of Byzantium (527-565), during which time Pope Vigilius himself happened to be in Constantinople by order of the Emperor. Jordanes dedicated his work to another man of religion, an otherwise unknown “brother Castalius” (or “Castulus”). To judge from his extremely negative attitude toward Arian Christianity (a heresy started by a priest named Arius), it is very likely that Jordanes had himself once been an Arian like most of the Goths, and that he had later converted to Catholicism. The Getica was written after beginning and before finishing a similar work on Roman history, the Romana, dedicated to a certain “most noble brother Vigilius” (probably not the pope of that name). By 551 the Gothic kingdom established by Theodoric (Þiuda-reik) had been destroyed, and the Western Roman Empire was disintegrating rapidly. The main aim of both treatises was to show how even the greatest structures of human power on this earth — whether Gothic or Roman — are transient and deceptive, and that man can find lasting peace in God alone. I have also translated and included the final sections of Jordanes’ Romana (## 367-388), portions which treat of Emperor Justinian’s war against the Goths in Italy and which both supplement and recapitulate some of the material found in the Getica. Senator Cassiodorus very likely destroyed his own 12-volume work because it had been written during the reign of Theodoric (493-526) and had treated the Goths very favorably, but shortly after Theodoric’s death the political climate had changed and Cassiodorus, formerly Theodoric’s Chief of Staff, now found himself in Constantinople, the seat of anti-Gothic sentiment. To avoid being seen as an enemy of the Empire, he therefore probably eliminated any traces of his former allegiance, which included his volumes on the Goths. Jordanes was in fact able to read the work only through the good graces of Cassiodorus’ steward, not Cassiodorus himself. Of this, James J. O’Donnell, in his web-published “The Aims of Jordanes,” observes that Jordanes “has only managed to lay his hands on the twelve books of Cassiodorus for three days and now must write from memory. The plain sense of the business about the steward is that Cassiodorus was not inclined to cooperate with such a project at this time and that it was carried out without his knowledge.” Jordanes’ work, which may be seen as a kind of obituary of the Gothic nation, contains a number of elements surprising and interesting to the modern reader. Besides its extensive portrayals of Attila the Hun and his battles (especially the historic battle of the Catalaunian Fields), it includes (Second Half, sections 237/8) one of the earliest references to the original “King Arthur,” known here as “Riotimus” (from Celtic *Rigo-tamus “King-most,” “Supreme king,” later literarily confused with a Latin name, Artorius). Likewise, many of the events and dramatis personae sung about in the epic lays and sagas of the later Germanic north are described here as they originally happened. Above all, the ceaseless battles and unending bloodshed described here give us some idea of just what the decline of a civilization entails. To follow the wanderings and adventures of the Goths, the best available atlas is the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, edited by Richard J.A. Talbert (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). This excellent volume is based on work by many scholars using both archeology and satellite-generated aeronautical charts to depict the ancient landscape as it was in the days of the Roman Empire, and is an immense help in understanding the topography of Europe traversed by the Goths. The Getica contains four main divisions: 1) a Geographical Introduction; 2) the United Goths; 3) the Visigoths; 4) the Ostrogoths. These sections are interspersed with sundry digressions of various sorts. The following texts are as follows: The Latin is based on that of Theodore Mommsen, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, which I have modified extensively for easier reading, since Jordanes’ own text is anything but “classical” in form. Many of the changes I have made in case endings are taken from the source Mommsen designates as “A,” meaning a codex of the 11th/12th century from the Ambrosian library in Milan, Italy. (“A” contains a number of other histories besides Jordanes, and it “corrects” many of the grammatical mistakes of the original from which it was copied.) Other changes are my own, such as substituting, in the interest of clarity in an often unclear Latin text, the form quum for the conjunction cum to distinguish it from the preposition cum. Likewise I have substituted the letter “J” for consonantal “I” and “æ” for “ae” as well as “œ” for “oe,” et cetera. The English is, with some exceptions, mainly that of Charles Christopher Mierow, Ph.D., 1915, altered in particular with respect to Germanic and especially Gothic names, all of which I have normally presented in modified Visigothic format (e.g., ð for the voiced labio-dental fricative instead of Biblical Visigothic d, -ing- for -igg-) for the sake of consistency. Also helpful in many instances was the sometimes more literal German translation by Dr. Wilhelm Martens, Jordanis Gotengeschichte, nebst Auszügen aus seiner Römischen Geschichte, herausgegeben von Alexander Heine, 1914, now available from the Phaidon Verlag in Essen, Germany. Other modifications will be obvious to the reader.

A few names which Jordanis uses are clearly mangled from those of much earlier historical characters. Some typical examples are “Dicineus” for “Decæneus” (§39), “Vesosis” for the original “Sesostris” (§§44, 47) and “Tanausis” for the original “Tanaos” (§47, 48). I have substituted the original forms of the names in both the Latin and the English. The grammar of the Latin, as found in the various manuscripts, is, frankly, a mess. An earlier editor, Karl Augustus Closs, in his Jordanis de Getarum sive Gothorum Origine et Rebus Gestis, Stuttgart, 1861, pp. ii-iii, complains of “grassatum esse et temporis vim injuriamque, et libariorum hominum incuriam negligentiam, stuporem, inscitiam, quandoque etiam licentiam” (“the criminal spreading of both the force and damage of time, and the inattentiveness of copyists, their negligence, stupor, ignorance and sometimes even their willfulness”). A small example, chosen at random, is the form Mommsen (1882) prints as expertes in VI, 69. As it stands, this form is the accusative plural of expers, “having no part in, not sharing in, destitute of,” but what is clearly meant (and actually appears in some of the lesser manuscripts) is expertos, masculine accusative plural of expertus “knowledgeable, experienced, proven (in)” (which takes the genitive case), the adjectivalized past participle passive of experiri “to (put to the) test; learn/know by trial and experience.” The meaning of the sentence in which the word is embedded is clearly “By instructing them in logic, he (Decænus) made them skilled in reasoning beyond other peoples,” not “destitute/shorn of.” Closs shows expertos, but Mommsen, judging by the weight of the otherwise best manuscripts, has expertes. In the following HTML version, the choice followed by Closs is used, since the purpose here is to present a text which presents as few difficulties as possible to readers of Latin who are not specialists in the field. There are a few instances where a suggestion made by Closs is used, such as, at XXX, 152, the substitution of sollicitationem (which I have translated as “plights”) for the manuscript pollicitationem (“promises”), since the latter word seems, as Closs notes, corrupt, given that Ala-reik had not “promised” anything but rather presented Emperor Honorius with the horns of a dilemma. This HTML edition is made not for scholars but for the general reader interested in European and Germanic history. It is, accordingly, not a “diplomatic” text (for which, see Mommsen) as found in the manuscripts, but, as already mentioned, a largely “emended” and “normalized” one, with misspellings corrected, missing case endings resupplied, etc. Finally, the punctuation follows American English conventions, not European ones. The extant manuscripts of Jordanes show a great deal of variation, confusion and inconsistency in the orthography of non-Graeco-Roman names (and, sometimes, even of classical Latin ones). Because of this, the spelling of most Germanic (Gothic, Frankish, Vandal, etc.) names is taken from M. Schönfeld, Wörterbuch der altgermanischen Personen- und Völkernamen, nach der Überlieferung des klassischen Altertums bearbeitet, zweite, unveränderte Auflage (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1965):

In many cases where the Germanic names contained a /w/ (e.g., Wulfila, Amalaswinþo), the Latin alphabet had not yet developed a “double-U” (thus resulting in Vulfila, Amalasuentha, &c.); in such cases, the letter “W/w” is here employed. Given that the manuscripts often confuse the letters “b” and “v/u” (e.g., manuscript Danuvius XLII, 223 vs. Danubius elsewhere, or Bulsiniensis LIX, 306 vs. classical Volsiniensis, spellings here corrected), this should make the pronunciation of these names a bit clearer. The reader who is interested in the manuscript presentations of these names is encouraged to consult Mommsen’s edition. Ancient letters:

NOTE: Jordanes plagiarized the first sentences of his Getica from the preface of Tyrannius Rufinus of Aquileja to a translation of Origen’s commentary on Romans. The plagiarized parts are here italicized. A few notes have been interspersed which are translations from Byzantine Greek authors as given in The Fragmentary Classicizing Historians of the Later Roman Empire: Eunapius, Olympiodorus, Priscus and Malchus. Vol. II, Text, Translation and Historiographical Notes, by R.C. Blockley (Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Fancis Cairns, Redwood Burn Ltd, 1983). |

| DE ORIGINE ACTIBUSQUE GETARUM | THE ORIGIN AND DEEDS OF THE GOTHS | ||||

| 1 | |||||

| Volentem me parvo subvectum navigio oram tranquilli litoris stringere et minutos de priscorum, ut quidam ait, stagnis pisciculos legere, in altum, frater Castali, laxare vela compellis, relictoque opusculo quod intra manus habeo — id est, de abbreviatione Chronicorum — suades, ut nostris verbis duodecim Senatoris volumina de origine actibusque Getarum ab olim et usque nunc per generationes regesque descendentia in unum et hunc parvum libellum coartem. | Though it had been my wish to glide in my little boat by the shore of a peaceful coast and (as someone once said) to gather little fishes from the pools of the ancients, you, brother Castalius, bid me set my sails toward the deep. You urge me to leave the little work I have in hand — that is, an abridged version of the Chronicles — and to condense in my own words in this one small book the twelve volumes of the Senator {Cassiodorus} on the origin and deeds of the Goths from olden time all the way to the present, descending through the generations of the kings. | ||||

| 2 | |||||

| Dura satis imperia et tanquam ab eo qui pondus operis hujus scire nollit imposita. Nec illud aspicis, quod tenuis mihi est spiritus ad implendam ejus tam magnificam dicendi tubam: super omne autem pondus, quod nec facultas eorundem librorum nobis datur, quatenus ejus sensui inserviamus, sed — ut non mentiar — ad triduanam lectionem, dispensatoris ejus beneficio, libros ipsos antehac relegi. Quorum, quamvis verba non recolo, sensus tamen et res actas credo me integre retinere. | Truly a hard command, and imposed by one who seems unwilling to realize the burden of the task. Nor do you note this, that my breath is too slight to fill so magnificent a trumpet of speech as his. But above every burden is the fact that I have no access to his books that I may follow his thought. Still — and let me lie not — some while ago I read the books a second time by his steward’s loan for a three days’ reading. The words I recall not, but the sense and the deeds related I think I retain entire. | ||||

| 3 | |||||

| Ad quos et ex nonnullis historiis Græcis ac Latinis addidi convenientia, initium finemque et plura in medio mea dictione permiscens. | To this I have added fitting matters from some Greek and Latin histories. I have also put in an introduction and a conclusion, and have inserted many things of my own authorship. | ||||

| Quare, sine contumelia quod exegisti suscipe libens, libentissime lege ; et si quid parum dictum est et tu, ut vicinus genti, commemoras, adde — orans pro me, frater carissime. Dominus tecum. Amen. | Wherefore reproach me not, but receive and read with gladness what you have asked me to write. If aught be insufficiently spoken and you remember it, do you as a neighbor to our race add to it, praying for me, dearest brother. The Lord be with you. Amen. | ||||

|

I (Geographical Introduction) 1 |

|||||

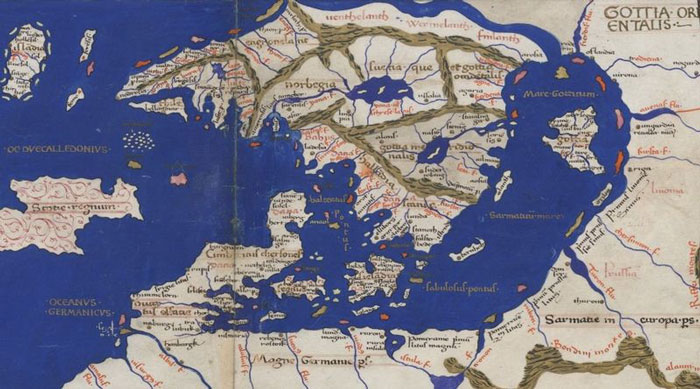

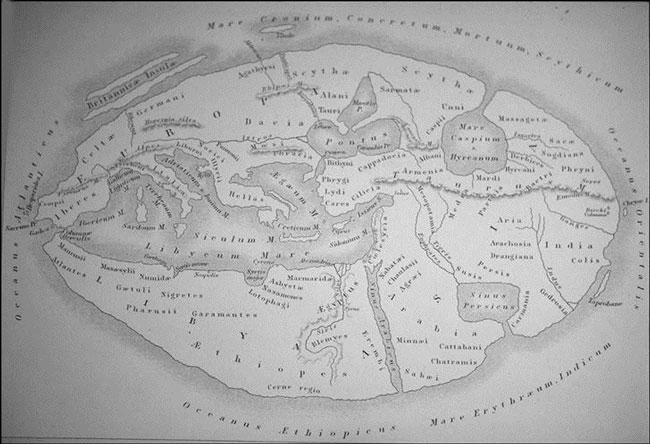

| Majores nostri, ut refert Orosius, totius terræ circulum Oceani limbo circumsæptum triquetrum statuerunt, ejusque tres partes Asiam, Europam et Africam vocaverunt. De quo tripertito orbis terrarum spatio innumerabiles pæne scriptores exsistunt, qui non solum urbium locorumve positiones explanant, verum etiam — et quod est liquidius — passuum miliariumque dimetiuntur quantitatem. Insulas quoque, marinis fluctibus intermixtas, tam majores quam etiam minores quas Cycladas vel Sporadas cognominant, in immenso maris magni pelago sitas determinant. | Our ancestors, as Orosius relates, were of the opinion that the circle of the whole world was surrounded by the girdle of Ocean on three sides. Its three parts they called Asia, Europe and Africa. Concerning this threefold division of the earth’s extent there are almost innumerable writers who not only explain the locations of cities and places, but also measure out the number of miles and paces to make it clearer. Moreover they locate the islands interspersed amid the waves, both the greater and also the lesser islands, called Cyclades or Sporades, as situated in the vast flood of the Great Sea. | ||||

| 5 | |||||

| Oceani vero intransmeabiles ulteriores fines non solum describere quis aggressus non est, verum etiam nec cuiquam licuit transfretare quia, resistente ulva, et ventorum spiramine quiescente, impermeabilis esse sentitur et nulli cognita nisi Ei Qui eam constituit. | But the impassable farther bounds of Ocean not only has no one attempted to describe, but no man has been allowed to reach; for by reason of obstructing seaweed and the failing of the winds it is plainly inaccessible and is unknown to any save to Him Who made it. | ||||

| 6 | |||||

| Citerior vero ejus pelagi ripa, quam diximus totius mundi circulum, in modum coronæ ambiens fines ejus, curiosis hominibus et qui de hac re scribere voluerunt perquaquam innotuit, quia et terræ circulus ab incolis possidetur et nonnullæ insulæ in eodem mare habitabiles sunt, ut in orientali plaga et Indico Oceano Hippodes, Iamnesia, Sole Perusta (quamvis inhabitabilis, tamen omnino sui spatio in longo latoque extensa); Taprobane quoque, exceptis oppidis vel possessionibus, decem munitissimis urbibus decora ; | But the nearer border of this sea, which we call the circle of the world, surrounds its coasts like a wreath. This has become clearly known to men of inquiring mind everywhere, even to such as desired to write about it. For not only is the coast itself inhabited, but certain islands off in the sea are habitable. Thus there are to the East in the Indian Ocean, Hippodes, Iamnesia, Sole Perusta {“Sunbake”} (which though not habitable, is yet of great length and breadth) and also Taprobane {Šri Lanka}, a fair island adorned with ten strongly fortified cities, not counting the towns or estates. | ||||

| 7 | |||||

| sed et aliæ omnino nominatissimæ, Silefantina, nec non et Theron — licet non ab aliquo scriptore dilucidæ, tamen suis possessoribus affatim refertæ. | But there are yet others: the very famous Silefantina, and Theros also. These, though not celebrated by any writer, are nevertheless well filled with inhabitants. | ||||

| Habet in parte occidua idem Oceanus aliquantas insulas et pæne cunctis ob frequentiam euntium et redeuntium notas. | This same Ocean has in its western region certain islands known to almost everyone by reason of the great number of those that journey to and fro. | ||||

| Et sunt juxta fretum Gaditanum haud procul una, Beata, et alia quæ dicitur Fortunata. | And there are two not far from the neighborhood of the Strait of Gades, one the Blessed Isle and another called the Fortunate. | ||||

| Quamvis nonnulli et illa gemina Gallæciæ et Lusitaniæ promuntoria inter Oceani insulas ponant, in quorum uno Templum Herculis, in alio Monumentum adhuc conspicitur Scipionis — tamen, quia extremitatem Gallæciæ terræ continent, ad terram magnam Europæ potius quam ad Oceani pertinent insulas. | Although some reckon as islands of Ocean the twin promontories of Galicia and Lusitania, where are still to be seen the Temple of Hercules on one and Scipio’s Monument on the other, yet since they encompass the extremity of the Galician country, they belong rather to the great land of Europe than to the islands of Ocean. | ||||

| 8 | |||||

| Habet tamen et alias insulas interius in suo æstu quæ dicuntur Baleares, habetque et aliam Menaviam, nec non Orcadas numero XXXIII quamvis non omnes excultas. | However, it has other islands deeper within its own tides, which are called the Baleares; and yet another, Menavia {the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea}, as well as the Orcades {the Orkneys}, 33 in number, though not all inhabited. | 9 | |||

| Habet et in ultimo < fine > plagæ occidentalis aliam insulam nomine Thule, de qua Mantuanus inter alia: “tibi serviat ultima Thule.” [Vergilius, Georgica 1,30] Habet quoque id ipsum immensum pelagus in parte arctoa — id est, septentrionali — amplam insulam nomine Scandiam, unde Nobis sermo (si Dominus juvaverit) est assumendus ; quia gens cujus originem flagitas ab hujus insulæ gremio velut examen apium erumpens in terram Europæ advenit ; quomodo vero aut qualiter, in subsequentibus (si Dominus donaverit) explanabimus. |

And at the farthest bound of its western expanse it has another Island named Thule {Mainland, the largest of the Shetland Islands north of Britain}, of which the Mantuan bard makes mention:

“And Farthest Thule shall serve thee.” [Virgil, Georgics 1,30] The same mighty sea has also in its arctic region, that is in the north, a great island named Scandia, from which my tale (by God’s grace) shall take its beginning. For the race whose origin you ask to know burst forth like a swarm of bees from the midst of this island and came into the land of Europe. But how or in what wise we shall explain hereafter, if it be the Lord’s will. |

||||

| II 10 |

|||||

| Nunc autem de Britannia insula, quæ in sinu Oceani inter Hispanias, Gallias et Germaniam sita est, ut potuero, paucis absolvam. | But now let me speak briefly as I can concerning the island of Britain, which is situated in the bosom of Ocean between Spain, Gaul and Germany. | ||||

| Cujus licet magnitudinem olim nemo, ut refert Livius, circumvectus est, multis tamen data est varia opinio de ea loquendi. | Although Livy tells us that no one in former days sailed around it because of its great size, yet many writers have held various opinions of it. | ||||

| Quam, diu siquidem armis inaccessam, Romanis Julius Cæsar prœliis, ad gloriam tantum quæsitis, aperuit ; pervia deinceps mercimoniis aliasque ob causas multis facta mortalibus, non indiligenti quæ secuta est ætati certius sui prodidit situm — quem, ut a Græcis Latinisque auctoribus accepimus, persequimur. | Although long unapproached by Roman arms, Julius Cæsar opened it up by battles fought for mere glory. Having been made accessible from then on to many people for trade and other purposes, it more clearly revealed its position to the busy period which followed — a position I shall here explain as I have found it in Greek and Latin authors. | ||||

| 11 | |||||

|

|||||

| Triquetram eam plures dixere consimilem, inter septentrionalem occidentalemque plăgam projectam, uno, qui magnus est, angulo Rheni ostia spectantem ; dehinc, correpta latitudine, oblique retro abstractam in duos exire alios ; geminoque latere longiorem Galliæ prætendi atque Germaniæ. | Most of them have said it is like a triangle pulled between north and west ; that at its obtuse angle it faces the mouths of the Rhine ; that from there, narrowing its widths, it tapers backwards on slants, ending in two other angles ; and that the longer coastline with its double legs stretches opposite Gaul and Germany. | ||||

| {Note} The island of Britain (Britannia insula): Pomponius Mela, Description of the World: Book III: “Around the World — the Circle of Ocean from the Pillars of Hercules,” Chapter 3 “Islands,” §§50f.: “Moreover, just as we have thought until now, Britain projects between the west and the north in a wide angle and looks toward the mouths of the Rhenus. It then draws its sides back obliquely, facing Gaul with one side, Germany with the other; then returning with a continuous line of straight shore on its rear side, Britain again wedges itself into two different angles — being triangular and very much like Sicily.” in: Pomponius Mela’s Description of the World, by Frank E. Romer. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1998, pp. 115f.) | |||||

| In duobus milibus trecentis decem stadiis latitudo ejus ubi patentior, longitudo non ultra septem milia centum triginta duo stadia fertur extendi ; | Its greatest breadth is said to be over two thousand three hundred and ten {2,310} stadia {= 265 miles (actually ~298 miles)}, and its length not more than seven thousand one hundred and thirty-two {7,132} stadia {= 820 miles (actually ~600 miles)}. | ||||

| 12 | |||||

| modo vero dumosa, modo silvestri jacere planitie, montibus etiam nonnullis increscere ; mari tardo circumflua, quod nec remis impellentibus facile cedat, nec ventorum flatibus intumescat — credo, quia remotæ longius terræ causas motibus negant ; quippe illic latius quam usquam æquor extenditur. | In some parts it lies fallow with briar thickets, in others with woods, and sometimes it rises into mountain peaks. The island is surrounded by a sluggish sea, which neither gives readily to the stroke of the oar nor runs high under the blasts of the wind. I suppose this is because other lands are so far removed from it as to cause no disturbance of the sea, which indeed is of greater width here than anywhere else. | ||||

| Refert autem Strabo, Græcorum nobilis scriptor, tantas illam exhalare nebulas, madefacta humo Oceani crebris excursibus, ut subtectus sol per illum pæne totum fœdiorem — qui « serenus » est — diem negetur aspectui. | Moreover Strabo, a famous writer of the Greeks, relates that the island exhales such mists from its soil, soaked by the frequent inroads of Ocean, that the sun is covered throughout the whole of their miserable sort of day that passes as fair, and so is hidden from sight. | ||||

| {Note} The sun is covered (subtectus sol): Strabo, Geography: Book IV, Chapter 5, §2: “Their weather is more rainy than snowy; and on the days of clear sky fog prevails so long a time that throughout a whole day the sun is to be seen for only three or four hours round about midday.” | |||||

| 13 | |||||

| Noctem quoque clariorem in extrema ejus parte minimamque, Cornelius etiam Annalium scriptor enarrat ; metallis plurimis copiosam, herbis frequentem et his feraciorem omnibus quæ pecora magis quam homines alant ; labi vero per eam multa quam maxima relabique flumina, gemmas margaritasque volventia. | Cornelius also, the author of the Annals, says that in the farthest part of Britain the night gets brighter and is very short. He also says that the island abounds in metals, is well supplied with grass and is more productive in all those things which feed beasts rather than men. Moreover many large rivers flow back and forth through it, rolling along precious stones and pearls. | ||||

| Silurum colorati vultus ; torto plerique crine et nigro nascuntur ; Caledoniam vero incolentibus rutilæ comæ, corpora magna, sed fluvida: Gallis sive Hispanis, ut quibusque obtenduntur, assimiles. | The Silures have swarthy features and are usually born with curly black hair, but the inhabitants of Caledonia {= the Scottish Highlands} have reddish hair and large but flaccid bodies. They are like the Gauls or the Spaniards, according as they are opposite either nation. | ||||

| 14 | |||||

| Unde conjectavere nonnulli, quod ea < insula > ex his accolas contiguo vocatos acceperit. | Hence some have supposed that from these lands the island received its inhabitants, alluring them by its nearness. | ||||

| Inculti æque omnes populi regesque populorum ; cunctos tamen in Caledoniorum Mæatarumque cessisse nomina Dio auctor est, celeberrimus scriptor annalium. | All the people and their kings are alike wild. Yet Dio, a most celebrated writer of annals, assures us of the fact that they have all been combined under the name of Caledonians and Mæatæ. | ||||

| Virgeas habitant casas, communia tecta cum pecore, silvæque illis sæpe sunt domus. | They live in wattled huts, a shelter used in common with their flocks, and often the woods are their home. | ||||

| Ob decorem, nescio an aliam quamobrem, ferro pingunt corpora. | They tatoo their bodies with iron-red, whether by way of adornment or perhaps for some other reason. | ||||

| 15 | |||||

| Bellum inter se, aut imperii cupidine aut amplificandi quæ possident, sæpius gerunt, non tantum equitatu vel pedite, verum etiam bigis curribusque falcatis, quos more vulgari « essedas » vocant. | They often wage war with one another, either out of lust for dominance or to increase their possessions. They fight not only on horse back or on foot, but even with scythed two-horse chariots, which they commonly call “essedæ.” | ||||

| Hæc pauca de Brittaniæ insulæ forma dixisse sufficiat. | Let it suffice to have said thus much on the shape of the island of Britain. | ||||

| III 16 |

|||||

| Ad Scandiæ insulæ situm, quod superius {I, 9} reliquimus, redeamus. | Let us now return to the site of the island of Scandia, which we left above {I, 9}. | ||||

| |||||

| De hac etenim in secundo sui operis libro Claudius Ptolomæus, orbis terræ descriptor egregius, meminit dicens: « Est in Oceani arctoi salo posita insula magna, nomine Scandia, in modum folii citri, lateribus pandis, per longum ducta concludens se ». | Claudius Ptolemæus, an excellent describer of the world, has made mention of it in the second book of his work, saying: “There is a great island situated in the surge of the northern Ocean, Scandia by name, in the shape of a citron leaf, with bulging sides that taper down to a point at a long end.” | ||||

| De qua et Pomponius Mela in maris sinu Codano positam refert, cujus ripas influit Oceanus. | Pomponius Mela also makes mention of it as situated in the Codan Gulf {= one of the gulfs and bays around the Jutland peninsula (the Kattegat?)} of the sea, with Ocean lapping its shores. | ||||

| 17 | |||||

| Hæc a fronte posita est Vistulæ fluminis quod, Sarmaticis montibus ortum, in conspectu Scandiæ septentrionali Oceano trisulcum illabitur, Germaniam Scythiamque disterminans. | This island lies opposite the river Vistula, which rises in the Sarmatian mountains {the Carpathian range} and flows through its triple mouth into the northern Ocean in sight of Scandia, separating Germany and Scythia. | ||||

| Hæc ergo habet ab oriente vastissimum lacum in orbis terræ gremio, unde Vagi fluvius velut quodam ventre generatus in Oceanum undosus evolvitur. | The island has in its eastern part a vast lake in the bosom of the earth, whence the Vagus {perhaps the Gotaälv river flowing from the Vänern lake} river springs from the bowels of the earth and flows surging into the Ocean. | ||||

| Ab occidente namque immensu pelago circumdatur, a septentrione quoque innavigabili eodem vastissimo concluditur Oceano, ex quo quasi quodam bracchio exiente, sinu distento, Germanicum mare efficitur. [In margine codicis O: Hic gentes quæ carnibus tantum vivunt.] | And on the west it is surrounded by an immense sea. On the north it is bounded by the same vast unnavigable Ocean, from which the German Sea {the North Sea} is formed by means of a protruding bay as though by a kind of outstretched arm. [In the margin of manuscript O: Here there are peoples who live only on meat.] | ||||

| 18 | |||||

| Ubi etiam parvæ quidem, sed plures perhibentur insulæ esse dispositæ ad quas si congelato mari ob nimium frigus lupi transierint, luminibus feruntur orbari. Ita non solum inhospitalis hominibus, verum etiam beluis terra crudelis est. | Here also there are said to be many small islands scattered round about. If wolves cross over to these islands when the sea is frozen by reason of the great cold, they are said to lose their sight. Thus the land is not only inhospitable to men but cruel even to wild beasts. | ||||

| 19 | |||||

| In Scandia vero insula, unde nobis sermo est, licet multæ et diversæ maneant nationes, septem tamen earum nomina meminit Ptolemæus. Apium ibi turba mellifica ob nimium frigus nusquam repperitur. In cujus parte arctoa gens AlogiR {= Halogii} consistit, quæ fertur in æstate media quadraginta diebus et noctibus luces habere continuas, itemque brumali tempore eodem dierum noctiumque numero lucem claram nescire. | Now in the island of Scandia, whereof I speak, there dwell many and diverse nations, though Ptolemæus mentions the names of but seven of them. There the honey-making swarms of bees are nowhere to be found on account of the exceeding great cold. In the northern part of the island the race of the Halogians {= inhabitants of Halogaland in northern Norway} live, who are said to have continual light in mid summer for forty days and nights, and who likewise have no clear light in the winter season for the same number of days and nights. | ||||

| 20 | |||||

| Ita, alternato mærore cum gaudio, beneficio aliis damnoque impar est. | By reason of this alternation of sorrow and joy they are unlike other races in their blessings and sufferings. | ||||

| Et hoc quare? Quia prolixioribus diebus solem ad orientem per axis marginem vident redeuntem, brevioribus vero non sic conspicitur apud illos, sed aliter, quia austrina signa percurrit, et qui nobis videtur sol ab imo surgere, illos per terræ marginem dicitur circuire. | And why? Because during the longer days they see the sun returning to the east above the horizon at the north pole, but on the shorter days it is not seen among them; but instead, because it passes through the southern constellations, the sun, which to us seems to rise from below, is said to circle them along the horizon. | ||||

| 21 | |||||

| Aliæ vero ibi sunt gentes: Scrithifinni, qui frumentorum non queritant victum, sed carnibus ferarum atque ovis avium vivunt ; ubi tanta paludibus fetura ponitur, ut et augmentum præstent generi et satietatem ad copiam genti. | There also are other peoples. There are the Scriþi-Fennæ {= “Schreit-Finnen,” “Walking Finns,” i.e., “Skiing Finns, Lapps, Ski-users”}, who do not seek grain for food but live on the flesh of wild beasts and birds’ eggs; for there are such multitudes of young game in the swamps as to provide for the natural increase of their kind and to afford satisfaction to the needs of the people. | ||||

| {Note} Scrithifinni (Mommsen Screrefennae): Procopius, History of the Wars: Book VI: The Gothic War XV, 420f. (PROCOPIUS, with an English Translation by H.B. Dewing, London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1919): “But among the barbarians who are settled in Thule, one nation only, who are called the Scrithiphini, live a kind of life akin to that of the beasts. For they neither wear garments of cloth nor do they walk with shoes on their feet, nor do they drink wine nor derive anything edible from the earth. For they neither till the land themselves, nor do their women work it for them, but the women regularly join the men in hunting, which is their only pursuit. For the forests, which are exceedingly large, produce for them a great abundance of wild beasts and other animals, as do also the mountains which rise there. And they feed exclusively upon the flesh of the wild beasts slain by them, and clothe themselves in their skins, and since they have neither flax nor any implement with which to sew, they fasten these skins together by the sinews of the animals, and in this way manage to cover the whole body. And indeed not even their infants are nursed in the same way as among the rest of mankind. For the children of the Scrithiphini do not feed upon the milk of women nor do they touch their mother's breast, but they are nourished upon the marrow of the animals killed in the hunt, and upon this alone. Now as soon as a woman gives birth to a child, she throws it into a skin and straightway hangs it to a tree, and after putting marrow into its mouth she immediately sets out with her husband for the customary hunt. For they do everything in common and likewise engage in this pursuit together. So much for the daily life of these barbarians.” | |||||

| Alia vero gens ibi moratur, Sweans, quæ velut Thuringi equis utuntur eximiis. | But still another race dwells there, the Swedes, who, like the Þuringos {(“-ingos” [“progeny”] spelled “-iggos” in Gothic) “Race of the Bold”}, have splendid horses. | ||||

| Hi quoque sunt, qui in usibus Romanorum sapphirinas pelles, commercio interveniente, per alias innumeras gentes transmittunt, famosi pellium decora nigredine. Hi quum inopes vivunt, ditissime vestiuntur. | Here also are those who send through innumerable other tribes the sapphire-colored skins to trade for Roman use. They are a people famed for the dark beauty of their furs and, though living in poverty, are most richly clothed. | ||||

| 22 | |||||

| Sequitur deinde diversarum turba nationum: Theustes, WagoR, BergjoR, HallinR, Liothida — quorum omnium sedes similiter planæ ac fertiles, et propterea inibi aliarum gentium incursionibus infestantur. | Then comes a throng of various nations, Þeustes {inhabitants of the region of Þiust, modern Tjust}, WagoR {inhabitants of the region of Wag}, BergjoR {inhabitants of the *bergaz “mountains”}, HallinR {inhabitants of the region of *hallus “rock”}, Lioþida. All their homelands are similarly level and fertile. Wherefore they are disturbed there by the attacks of other tribes. | ||||

| Post hos AhelmiR, Finn-haithæ, FerviR, Gauti-Goth {= « Gauthi Goþi »}, acre hominum genus et ad bella promptissimum. | Beyond these are the AhelmiR, Finn-haiþæ {= Finns of the Heath, the Prairie Finns}, FerviR and Gautigot {clarifying apposition: “Gauts, that is, the Goths”}, a race of men bold and quick to fight. | ||||

| Dehinc mixti Ewa-Greutingis. | Then come the mixed ones, the Ewa-Greutings {“Ever-Greutings,” “Longstanding Sand-dwellers”}. | ||||

| Hi omnes excisis rupibus quasi castellis inhabitant ritu beluino. | All these live like wild animals in rocks hewn out like castles. | ||||

| 23 | |||||

| Sunt et his exteriores Ostrogothæ, Raumariciæ, Rahnaricii, Finni mitissimi, Scandiæ cultoribus omnibus minores ; nec non et pares eorum WingulR; Switheudi, cogniti in hac gente reliquis corpore eminentiores: quamvis et Dani, ex ipsorum stirpe progressi, Erulos propriis sedibus expulerunt (quibus non ante multos annos Hrodwulf rex fuit, qui contempto proprio regno ad Theodorici Gothorum regis gremium convolavit et, ut desiderabat, invenit), qui inter omnes Scandiæ nationes nomen sibi ob nimiam proceritatem affectant præcipuum. | And there are beyond these the Ostrogoths, Rauma-reikians {= inhabitants of the SE Norwegian district of Rauma-ríki “domain of the Raumæ”}, Rahna-reikians {= inhabitants of the SE Norwegian district of Rán-ríki “domain of the Plunderers”}, and the most gentle Finns, lesser than all the inhabitants of Scandia. Like them are the Winguli {= inhabitants of Vingul-mǫrk} also. The Swi-þiuð {= “folk of the Swedes,” “Swede-folk”} are of this stock and excel the rest in stature. However, the Dani, who trace their origin to the same stock, drove from their homes the Aírulos {= “Men,” “Earls”}, who claim to be preëminent among all the nations of Scandia because of their tallness — and over whom Hroð-wulf {“Victorious wolf”} was king not many years ago. But he despised his own kingdom and fled to the embrace of Þiuda-reik {“People-ruler,” “Leader of the folk”}, king of the Goths, finding there what he desired. | ||||

| 24 | |||||

| Sunt quanquam et horum positura Granii, Agadii, Eunixi, Thelæ, Rugi, Harothi, Ranii. | Furthermore there are in the same neighborhood the Granii {= inhabitants of Gren-mar and Gren-land in southern Norway}, Agði {= inhabitants of Agðir in southern Norway}, Eunixi, Þilir {= inhabitants of Þela-mǫrk, now Telemarken in southern Norway}, Rugians {“Hard-strivers,” “Exerters,” “Toilers”}, Haruðes {= inhabitants of Horða-land around the Hardangerfjord, later on the lower Elbe} and Ranii. | ||||

| Hæ itaque gentes, Germanis corpore et animo grandiores, pugnabant beluina sævitia. | All these nations surpassed the Germans in size and spirit, and fought with the cruelty of wild beasts. | ||||

| IV (The United Goths) 25 |

|||||

| Ex hac igitur Scandia insula quasi officina gentium aut certe velut vagina nationum cum rege suo nomine Berig, Gothi quondam memorantur egressi: qui ut primum e navibus exeuntes terras attigerunt, ilico nomen loco dederunt. Nam hodieque illic, ut fertur, Gothisc-Andia vocatur. | Now from this island of Scandia, as from a factory of races or a vagina of nations, the Goths are said to have come forth long ago under their king, Baírika {“Bear-like”} by name. As soon as they disembarked from their ships and set foot on the land, they straightway gave their name to the place. And even to-day it is said to be called Gutisk-Andja {“Gothic End”}. | ||||

| 26 | |||||

| Unde mox promoventes ad sedes Hulme-Rugorum, qui tunc Oceani ripas insidebant, castra metati sunt, eosque, commisso prœlio, propriis sedibus pepulerunt, eorumque vicinos Wandalos jam tunc subjugantes suis applicavere victoriis. | Soon they moved from here to the abodes of the Hulm-Rugians {= “Island Rugians” [Rugii = “Hard-strivers,” “Exerters,” “Toilers”] on the islands in the mouth of the Vistula}, who then dwelt on the shores of Ocean, where they pitched camp, joined battle with them and drove them from their homes. Next they subdued their neighbors, the Vandals {“those who wind" or “those who turn/change”}, and thus added to their victories. | ||||

| Ubi vero magna populi numerositate crescente et jam pæne quinto rege regnante post Beric Filimer, filio Gadarici, consilio sedit ut exinde cum familiis, Gothorum promoveret exercitus. | But when the number of the people increased greatly and Fili-mer {“Very famous”}, son of Gaða-reik {“Comrade-prince”}, reigned as king — about the fifth since Baírika —, he settled on the plan that the army of the Goths with their families should move from that region. | ||||

| 27 | |||||

| Qui aptissimas sedes locaque quum quæreret congrua, pervenit ad Scythiæ terras quæ lingua eorum « Ojum » vocabantur, ubi delectatus magna ubertate regionum. Et exercitus medietate transposita, pons dicitur, unde amnem trajecerat, irreparabiliter corruisse, nec ulterius jam cuiquam licuit ire aut redire. | In search of suitable homes and pleasant places they reached the lands of Scythia, which in their tongue are called “Aujom” {“in the waterlands,” i.e., southern Russia and Ukraine}. Here they were delighted with the great richness of the country, and it is said that when half of the army had been brought over, the bridge whereby they had crossed the river collapsed irreparably, nor could anyone thereafter pass to or fro. | ||||

| Nam is locus, ut fertur, tremulis paludibus voragine circumjecta concluditur, quem utraque confusione natura reddidit impervium. | For the place is said to be surrounded by quaking bogs and an encircling abyss, so that by this double obstacle nature has made it inaccessible. | ||||

| Verumtamen hodieque illic et voces armentorum audiri et indicia hominum deprehendi, commeantium attestationem — quamvis a longe audientium —, credere licet. | Indeed, one might give credence to the assertions of travelers — even if they have heard it from afar — that in that area even today the lowing of cattle is heard and traces of men are found. | ||||

| 28 | |||||

| Hæc ergo pars Gothorum quæ apud Filimer — dicitur — in terras Ojum, emenso amne transposita, optato potita solo. | So having crossed the river, this part of the Goths which migrated with Fili-mēr {“Greatly famous,” “Much renowned”} into the territory of Aujom, they say, took possession of the desired land. | ||||

| Nec mora : ilico ad gentem Spalorum adveniunt, consertoque prœlio, victoriam adipiscuntur, exindeque jam velut victores ad extremam Scythiæ partem quæ Ponto mari vicina est properant — quemadmodum et in priscis eorum carminibus pæne historico ritu in commune recordantur, quod et Ablabius, descriptor Gothorum gentis egregius, verissima attestatur historia. | There they quickly came upon the race of the Spali {= Slavic for “the Giants”}, joined battle with them and won the victory. Thence the victors hastened to the farthest part of Scythia, which is near the sea of Pontus; for so the story is generally told in their early songs, in almost historic fashion. Ablabius also, a famous chronicler of the Gothic race, confirms this in his most trustworthy account. | ||||

| 29 | |||||

| In quam sententiam et nonnulli consensere majorum : Josephus quoque, annalium relator verissimus, dum ubique veritatis conservet regulam et origines causarum a principio revolvat. Hæc vero quæ diximus de gente Gothorum principia, cur omiserit, ignoramus : sed tantum Magog de eorum stirpe commemorans, Scythas eos et natione et vocabulo asserit appellatos. | Some of the ancient writers also agree with the tale. Among these we may mention Josephus {Jewish scholar and historian, † A.D. 95}, a most reliable relator of annals, who everywhere follows the rule of truth and unravels from the beginning the origins of causes; — but why he has omitted the beginnings of the race of the Goths, of which I have spoken, I do not know. He barely mentions Magog of that stock, and says they were Scythians by race and were called so by name. | ||||

| Cujus soli terminos, antequam aliud ad medium deducamus, necesse est, ut jacent, edicere. | Before we enter on our history, we must describe the boundaries of this land, as it lies. | ||||

| V 30 |

|||||

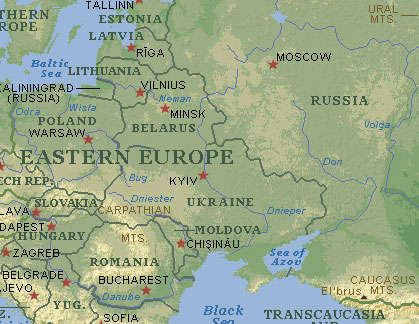

| Scythia, siquidem Germaniæ terræ confinis eo tenus ubi Hister oritur amnis vel stagnum dilatatur Morsianum, tendens usque ad flumina Tyram-Danastrum et Wagosolam, magnumque illum Danaprum Taurumque montem (non illum Asiæ, sed proprium, id est Scythicum) per omnem Mæotidis aditum, | Given that Scythia is bordered by Germany, where the Hister {eastern Danube} river starts or the Morsian swamp widens out, it stretches on to the rivers Dniestr and Bug as well as to the great Dniepr and the Taurus mountain range (not that of Asia Minor, but our own, the Scythian one) over all the approaches to the Sea of Asov; | ||||

| ultraque Mæotida, per angustias Bosphori, usque ad Caucasum montem amnemque Araxem, | and, on the other side of the Sea of Asov, across the Kerch Strait, all the way to the Caucasus range and the Araxes river; | ||||

| ac deinde in sinistram partem reflexa, post mare Caspium (quod in extremis Asiæ finibus ab Oceano euroboro in modum fungi, primum tenui, posthæc latissima et rotunda forma exoritur), vergens ad Hunnos, Albanos et Seres usque, digreditur. | then, turning to the left behind the Caspian Sea (which arises at the outermost edge of Asia from the northeastern ocean in a mushroom-like way, at first slender in shape, then very broad and round), it proceeds onward, extending as far as the Huns, Transcaucasians and Chinese. | ||||

| 31 | |||||

| Hæc, inquam, patria — id est Scythia —, longe se tendens lateque aperiens, habet ab oriente Seres, in ipso sui principio litus Caspii maris commanentes ; ab occidente Germanos et flumen Vistulæ; ab arcto — id est septentrionali — circumdatur oceano, a meridie Persida, Albania, Hiberia, Ponto atque extremo alveo Histri, qui dicitur Danubius ab ostio suo usque ad fontem. | This land, I say, — namely, Scythia, stretching far and spreading wide, — has to the east the Chinese, a race that at the very beginning of its history inhabited the shore of the Caspian Sea. To the west are the Germans and the river Vistula; on the Arctic side, namely the north, it is surrounded by ocean; to the south by Persians, Transcaucasians, Georgia, Asia Minor and the farthest channel of the Hister, which is called the Danube all the way from mouth to source. | ||||

|

|||||

| 32 | |||||

| In eo vero latere, qua Ponticum litus attingit, oppidis haud obscuris involvitur — Boristhenide, Olbia, Callipolida, Chersona, Theodosia, Careon, Myrmecion et Trapezunta —, quas indomitæ Scytharum nationes Græcis permiserunt condere, sibimet commercia præstaturos. | But in that region where Scythia touches the Pontic coast it is dotted with towns of no mean fame: Borysthenes, Olbia, Kallipolis, Kherson, Theodosia, Kareon {modern Kerch}, Myrmekion and Trapezus {modern Trebizond}. These towns the wild Scythian tribes allowed the Greeks to build to afford them means of trade. | ||||

| In cujus Scythiæ medium est locus, qui Asiam Europamque ab alterutra dividit, Rhiphæi scilicet montes, qui Tanaim vastissimum fundunt intrantem Mæotida, cujus paludis circuitus passuum milia CXLIIII {centum quadraginta quattuor}, nusquam octo ulnis altius subsidentis. | In the midst of Scythia is the place that separates Asia and Europe, I mean the Central Russian Upland {confused by the ancients with the Urals}, from which the mighty Don flows. This river enters the Sea of Asov, a marsh having a circuit of one hundred and forty-four miles and nowhere subsiding to a depth greater than eight fathoms. | ||||

| 33 | |||||

| In qua Scythia, prima ab occidente gens residet Gipedarum quæ magnis opinatisque ambitur fluminibus. | In the land of Scythia to the westward dwells, first of all, the race of the Gibiðos {“The Givers,” tauntingly misnamed as Gipidos, “The Slow, Dull ones”}, surrounded by great and famous rivers. | ||||

|

|||||

| Nam Tisia per aquilonem ejus caurumque discurrit ; ab africo vero magnus ipse Danubius, ab euro fluvius Aluta secat qui rapidus ac verticosus in Histri fluenta furens divolvitur. | For the Tisza {modern Theiss, in Hungary} flows through it on the north and northwest, and on the southwest is the great Danube. On the east it is cut by the Aluta river {in Hungary}, a swiftly eddying stream that sweeps swirling into the Hister’s waters. | ||||

| 34 | |||||

| Introrsus illis Dacia est, ad coronæ speciem arduis Alpibus emunita, juxta quarum sinistrum latus, quod in aquilonem vergit, ab ortu Vistulæ fluminis per immensa spatia Wenedarum natio populosa consedit. Quorum nomina, licet nunc per varias familias et loca mutentur, principaliter tamen Sclaweni et Antes nominantur. | Within these rivers lies Dacia, encircled by the lofty Alps as by a crown. Near their left ridge, which inclines toward the north, and beginning at the source of the Vistula, the populous race of the Winiþi dwell, occupying a great expanse of land. Though their names now vary amid various clans and places, yet they are chiefly called Sclaweni and Antes. | ||||

| 35 | |||||

| Sclaweni a civitate Noviodunensi et lacu qui appellatur Mursianus usque ad Danastrum, et in boream Vistula tenus, commorantur : hi paludes silvasque pro civitatibus habent. | The abode of the Sclaweni extends from the city of Noviodunum {“New Town,” modern Isaktscha, Romania} and the lake called Mursianus to the Dniestr, and northward as far as the Vistula. They have swamps and forests for their cities. | ||||

| Antes vero, qui sunt eorum fortissimi, qua Ponticum mare curvatur, a Danastro extenduntur usque ad Danaprum, quæ flumina multis mansionibus ab invicem absunt. | The Antes, who are the bravest of these peoples dwelling around the bend of the Black Sea, spread from the Dniestr to the Dniepr, rivers that are many days’ journey apart. | ||||

| 36 | |||||

| Ad litus autem Oceani, ubi tribus faucibus fluenta Vistulæ fluminis ebibuntur, Widiwarii resident, ex diversis nationibus aggregati ; post quos ripam Oceani item Æsti tenent, pacatum hominum genus omnino. | But on the shore of Ocean, where the floods of the river Vistula empty from three mouths, the Wiði-warii {= inhabitants of Wid-land, OE Wit-land} dwell, a people gathered out of various tribes. Beyond them the Æsti {= ancestors of the Estonians}, a completely peaceful folk, likewise hold the shore of Ocean. | ||||

| Quibus in austrum assidet gens Acatzirorum fortissima, frugum ignara, quæ pecoribus et venationibus victitat. | To the south dwell the Acatziri, a very brave tribe ignorant of agriculture, who subsist on their flocks and by hunting. | ||||

| 37 | |||||

| Ultra quos distenduntur supra mare Ponticum Bulgarum sedes, quos notissimos peccatorum nostrorum mala fecerunt. | Beyond them above the Black Sea stretch the lands of the Bulgars, whom the evils of our errors have made well known. | ||||

| Hinc jam Hunni, quasi fortissimarum gentium fecundissimus cæspes, bifaria populorum rabie pullularunt. | From here the Huns, like a kind of very fertile sod of exceedingly strong tribes, expanded with two-pronged ferocity against other peoples. | ||||

| Nam alii Altziagiri, alii Sabiri nuncupantur, qui tamen sedes habent divisas : juxta Chersonam Altziagiri, quo Asiæ bona avidus mercator importat ; qui æstate campos pervagantur, effusas sedes, prout armentorum invitaverint pabula, hieme supra mare Ponticum se referentes. | Some of these are called Altziagiri, others Sabiri; and they have separate dwelling places. The Altziagiri are near Kherson, where the avaricious trader brings in the goods of Asia. In summer they range the plains, their broad domains, wherever the pasturage for their cattle invites them, and in winter returning to over the Black Sea. | ||||

| Hunuguri autem hinc sunt noti, quia ab ipsis pellium murinarum venit commercium : quos tantorum virorum formidavit audacia. | Now the Hunuguri {“Hungarians,” lit. “Ten Tribes”} are known to us from the fact that they trade in ermine pelts. The audacity of the men mentioned above has intimidated them. | ||||

| 38 | |||||

| Gothorum mansione prima in Scythiæ solo juxta paludem Mæotidem, secunda in Mœsia Thraciaque et Dacia, tertia supra mare Ponticum rursus in Scythis legimus habitasse : | We read that in the Goths’s first stage they dwelt on Scythian soil next to the Sea of Azov, in the second in Mœsia, Thrace and Dacia, in the third again in Scythia above the Black Sea. | ||||

| Nec eorum fabulas alicubi repperimus scriptas qui eos dicunt in Britannia vel in unaqualibet insularum in servitutem redactos et unius caballi pretio a quodam ereptos. | Nowhere in writing do we find the tales of those who say they were reduced to slavery in Britain or one of the islands and redeemed at the cost of a single nag. | ||||

| Aut certe, si quis eos aliter dixerit in nostra urbe quam quod nos diximus fuisse exortos, nobis aliquid obstrepet. Nos enim potius lectioni credimus quam fabulis anilibus consentimus. | Of course if anyone in our city says that the Goths had an origin different from that I have related, in my view something will present an objection. Because I myself prefer to believe what I read rather than put trust in old wives’ tales. | ||||

| 39 | |||||

| Ut ergo ad nostrum propositum redeamus, in prima sede Scythiæ juxta Mæotidem commanentes præfati, unde loquimur, Filimer regem habuisse noscuntur ; | To return, then, to my subject. The aforesaid race of which I speak is known to have had Filimer as king while they remained in their first home in Scythia near the Sea of Asov. | ||||

| in secunda — id est Daciæ Thraciæque et Mœsiæ solo — Zalmoxen, quem miræ philosophiæ eruditionis fuisse testantur plerique scriptores annalium. | In their second home, that is, on the territories of Dacia, Thrace and Mœsia, Zalmoxes {an earth-god of the Getæ of Thrace} reigned, whom many writers of annals mention as a man of remarkable learning in philosophy. | ||||

| Nam et Zeutam prius habuerunt eruditum, post etiam Decæneum, tertium Zalmoxen, de quo superius diximus. | Yet even before this they had a learned man, Zeuta, and after him Decæneus; and the third was Zalmoxes of whom I have made mention above. | ||||

| Nec defuerunt qui eos sapientiam erudirent. | Nor was there a lack of those who taught them philosophy. | ||||

| 40 | |||||

| Unde et pæne omnibus barbaris Gothi sapientiores semper exstiterunt, Græcisque pæne consimiles, ut refert Dio qui historias eorum annalesque Græco stilo composuit. | Wherefore the Goths have ever been wiser than other barbarians and were nearly like the Greeks, as Dio relates who wrote their history and annals with a Greek pen. | ||||

| Qui dicit primum Tarabosteseos, deinde vocatos Pilleatos hos qui inter eos generosi exstabant, ex quibus eis et reges et sacerdotes ordinabantur. | He says that those of noble birth among them, from whom their kings and priests were appointed, were called first Tarabostesei and then Pilleati {“Felt-cap-wearers,” “Felt-bonneted,” actually members of the Getic-Thracian nobility, here identified by Jordanes with the Gothic rulership}. | ||||

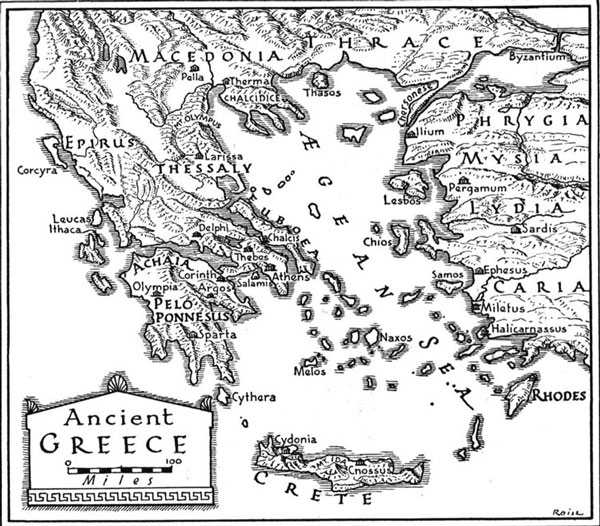

| Adeo ergo fuere laudati Getæ, ut dudum Martem, quem poëtarum fallacia deum belli pronuntiat, apud eos fuisse dicant exortum. | Moreover so highly were the Getæ praised that Mars, whom the falsehoods of poets call the god of war, was reputed to have been born among them. | ||||

| Unde et Vergilius : « Gradivumque patrem, Geticis qui præsidet arvis » {Æneidis 3,35}. |

Hence Virgil says: “and Father Gradivus {= Mars} who rules the Getic fields” {Æneid 3,35}. |

||||

| 41 | |||||

| Quem Martem Gothi semper asperrima placavere cultura (nam victimæ ejus mortes fuere captorum), opinantes bellorum præsulem apte humani sanguinis effusione placandum. | Now Mars has always been worshipped by the Goths with cruel rites, and captives were slain as his victims. They thought that he who is the lord of war needed to be appeased by the shedding of human blood. | ||||

| Huic prædæ primordia vovebant, huic truncis suspendebantur exuviæ, eratque illis religionis præter ceteros insinuatus affectus, quum parenti devotio numinis videretur impendi. | To him they devoted the first share of the spoil, and in his honor arms stripped from the foe were suspended from trees. And they had more than all other races a deep spirit of religion, since the worship of this god seemed to be really bestowed upon their ancestor. | ||||

| 42 | |||||

| Tertia vero sede super mare Ponticum jam humaniores et, ut superius diximus, prudentiores effecti, divisi per familias populi, Wisigothæ familiæ Balthorum, Ostrogothæ præclaris Amalis serviebant. | In their third dwelling place, which was above the Black Sea, they had now become more civilized and, as I have said before, were more learned. Then the people were divided under ruling families. The Visigoths {“the good, righteous, true, original Goths,” adherents of the old, heathen religion} served the family of the Balþi {“the Bold”} and the Ostrogoths {“the sprinkled, water-splashed, baptized Goths,” who had adopted Christianity} served the renowned Amali {“the Energetic”}. | ||||

| 43 | |||||

| Quorum studium fuit primum inter alias gentes vicinas arcum intendere nervis, Lucano plus historico quam poëta testante : « Armeniosque arcus Geticis intendere nervis ». {Pharsalia 8,221} |

They were the first race of men to string the bow with cords, as Lucan, who is more of a historian than a poet, affirms: “And stretch the Armenian bows with Getic strings.” {Pharsalia 8,221} |

||||

| Ante quos etiam cantu majorum facta modulationibus citharisque canebant, et Erpamaræ, Analæ, Frithigerni, Widigojæ et aliorum, quorum in hac gente magna opinio est, quales vix heroas fuisse miranda jactat antiquitas. | In earliest times they sang of the deeds of their ancestors in strains of song accompanied by the cithara; chanting of Erpa-marha {“Brown horse”}, Anala {“Grandfather”}, Friþi-gaírn {“Peace-yearning,” “Peace-desirous”}, Widu-gauja {“Woodland man,” “Forest-region dweller”} and others whose fame among them is great; such heroes as admiring antiquity repeatedly boasts that they were not just demigods. | ||||

| 44 | |||||

| Tunc, ut fertur, Sesostris Scythis lacrimabile sibi potius intulit bellum — eis videlicet, quos Amazonum viros prisca tradit auctoritas, de quibus feminis bellatricibus Orosius in primo volumine professa voce testatur. | Then, as the story goes, Sesostris {of Egypt, Rameses II, the Great, 1973-1928 B.C.} waged a war disastrous to himself against the Scythians — those, that is, whom ancient tradition asserts to have been the husbands of the Amazons. In his first book, Orosius attests to these warmaking women in authoritative language. | ||||

| Unde cum Gothis eum tunc dimicasse evidenter probamus quem cum Amazonum viris pugnasse cognoscimus absolute, qui tunc a Borysthene amne (quem accolæ « Danaprum » vocant) usque ad Tanain fluvium circa sinum paludis Mæotidis consedebant. | Thus we can clearly prove that at that time Sesostris fought with the Goths, since we know surely that he waged war with the Amazons’ husbands, who then dwelt along a bay of the Sea of Asov from the river Borysthenes (which the natives call the “Dniepr”) to the Don river. | ||||

| 45 | |||||

|

|||||

| Tanain vero hunc dico, qui ex Rhiphæis montibus dejectus adeo præceps ruit ut, quum vicina flumina sive Mæotis et Bosphorus gelu solidentur, solus amnium, confragosis montibus vaporatus, nunquam Scythico durescit algore, hic Asiæ Europæque terminus famosus habetur. | By the Don I mean the river which flows down from the Central Russian Uplands and rushes with so swift a current that when the neighboring streams or the Sea of Asov and the Kerch Strait are frozen fast, it is the only river that is kept warm by the rugged mountains and is never solidified by the Scythian cold. It is also famous as the boundary of Asia and Europe. | ||||

| Nam alter est ille qui, montibus Chrinnorum oriens, in Caspium mare dilabitur. | For the other Don {= the Volga} is the one which rises in the mountains of the Chrinni {= the Volga Hills? Ural Mountains? Actual source: Valday Hills northwest of Moscow} and flows into the Caspian Sea. | ||||

| 46 | |||||

| Danaper autem, ortus grande palude, quasi ex matre profunditur. | The Dniepr begins in a great marsh and issues from it as from its mother. | ||||

| Hic usque ad medium sui dulcis est et potabilis, piscesque nimii saporis gignit, ossibus carentes cartilaginem tantum habentes in corporis continentiam, sed ubi fit Ponto vicinior, parvum fontem suscipit, cui Exampæo cognomen est, adeo amarum ut, quum sit quadraginta dierum itinere navigabilis, hujus aquis exiguis immutetur, infectusque ac dissimilis sui inter Græca oppida Callipidas et Hypanis in mare defluat, ad cujus ostia insula est in fronte, Achillis nomine. | It is sweet and fit to drink as far as half-way down its course. It also produces fish of a fine flavor and without bones, having only cartilage as the supporting framework of their bodies. But as it approaches the Black Sea it receives a little spring called Exampæus {= “Sacred Roads” — Herodotus}, so very bitter that although the river is navigable for the length of a forty days’ voyage, it is so altered by the water of this scanty stream as to become tainted and unlike itself, and flows thus tainted into the sea between the Greek towns of Callipidæ {region on the river Tyras, modern Dniestr} and Hypanis {on the river Hypanis, modern Bug}. At its mouths there is an island named Achilles. | ||||

| Inter hos terra vastissima, silvis consita, paludibus dubia. | Between these two rivers is a vast land filled with forests and treacherous swamps. | ||||

| VI 47 |

|||||

| Hic ergo Gothis morantibus, Sesostris, Ægyptiorum rex, in bellum irruit, quibus tunc Tanaos rex erat, quo prœlio ad Phasim fluvium (a quo Phasides aves exortæ in toto mundo epulis potentum exuberant) Tanaos, Gothorum rex, Sesostri Ægyptiorum regi occurrit, eumque graviter debellans in Ægyptum usque persecutus est et, nisi Nili amnis intransmeabilis obstitissent fluenta, vel munitiones quas dudum sibi ob incursiones Æthiopum Sesostris fieri præcepisset, ibi in ejus eum patria exstinxisset.

Sed quum eum ibi positum non valuisset lædere, revertens pæne omnem Asiam subjugavit et sibi tunc caro amico Sorno, regi Medorum, ad persolvendum tributum subditos fecit, ex cujus exercitu victores tunc nonnulli, provincias subditas contuentes et in omni fertilitate pollentes, deserto suorum agmine, sponte in Asiæ partibus resederunt. |

This was the region where the Goths dwelt when Sesostris {I, 1973-1928 B.C.}, king of the Egyptians, made war upon them. Their king at that time was Tanaos {Scythian king after whom the Tanais [Don] was supposedly named; allegedly 1323-1290 B.C.}. In a battle at the river Phasis {= Rioni, southwest of the Caucasus} (whence come the birds called “pheasants,” which are found in abundance at the banquets of the powerful all over the world) Tanaos, king of the Goths, met Sesostris, king of the Egyptians, and there inflicted a severe defeat upon him, pursuing him all the way to Egypt. Had he not been restrained by the waters of the impassable Nile and the fortifications which Sesostris had long ago ordered to be made against the raids of the Ethiopians, he would have slain him in his own land.

But finding he had no power to injure him there, he returned and conquered almost all Asia Minor and made it subject and tributary to Sornus, king of the Medes, who was then his dear friend. At that time some of his victorious army, seeing that the subdued provinces were rich and fruitful, deserted their companies and of their own accord remained in various parts of Asia. |

||||

| 48 | |||||

| Ex quorum nomine vel genere Pompejus Trogus Parthorum dicit exstitisse prosapiam, unde etiam hodieque lingua Scythica « fugaces », quod est « Parthi », dicuntur, suoque generi respondentes inter omnes pæne Asiæ nationes soli sagittarii sunt et acerrimi bellatores. | From their name or race Pompejus Trogus {Roman historian of Gaulic or Vocontian descent, wrote the Historiæ Philippicæ in the Augustan period} says the stock of the Parthians had its origin. Hence even to-day in the Scythian tongue they are called “Parthi,” that is, “Deserters.” And in consequence of their descent they are archers — almost alone among all the nations of Asia — and are very valiant warriors. | ||||

| De nomine vero, quo diximus eos « Parthos », « fugaces », ita aliquanti etymologiam traxerunt, ut dicerentur « Parthi », quia suos refugerunt parentes. | Now in regard to the name, though I have said they were called “Parthi” because they were “deserters,” some have traced the derivation of the word otherwise, saying that they were called “Parthi” because they fled from their elders. | ||||

| Hunc ergo Tanaum regem Gothorum mortuum inter numina sui populi coluerunt. | Now when Tanaos, king of the Goths, was dead, his people worshipped him as one of their gods. | ||||

| VII 49 |

|||||

| Post cujus decessum, et exercitu ejus cum successoribus ipsius in aliis partibus expeditionem gerente, feminæ Gothorum a quadam vicina gente temptantur in prædam. | After his death, while the army under his successors was engaged in an expedition in other parts, a neighboring tribe attempted to carry off women of the Goths as booty. | ||||

| Quæ, doctæ a viris, fortiter restiterunt hostesque super se venientes cum magna verecundia abegerunt. | But they made a brave resistance, as they had been taught to do by their husbands, and routed in disgrace the enemy who had come upon them. | ||||

| Qua patrata victoria fretæque majore audacia, invicem se cohortantes arma arripiunt, eligentesque duas audentiores, Lampetonem et Marpesiam, principatui surrogarunt. | When they had won this victory, they were inspired with greater daring. Mutually encouraging each other, they took up arms and chose two of the bolder, Lampeto and Marpesia, to act as their leaders. | ||||

| 50 | |||||

| Quæ dum curam gerunt, ut et propria defenderent et aliena vastarent sortitæ, Lampeto restitit ad fines patrios tuendos, Marpesia vero, feminarum agmine sumpto, novum genus exercitus duxit in Asiam, diversasque gentes bello superans, alias vero pace concilians ; ad Caucasum venit, ibique certum tempus demorans loco nomen dedit « Saxum Marpesiæ », unde et Vergilius, « quam si dura silex aut stet Marpesia cautes », {Æneidis 6,471} in eo loco, ubi posthæc Alexander Magnus, portas constituens, « Pylas Caspias » nominavit, quas nunc Lazorum gens custodit pro munitione Romana. |

While they were in command, they cast lots both for the defense of their own country and the devastation of other lands. So Lampeto remained to guard their native land and Marpesia took a company of women and led this novel army into Asia. After conquering various tribes in war and making others their allies by treaties, she came to the Caucasus. There she remained for some time and gave the place the name “Rock of Marpesia,” of which also Virgil makes mention: “As if hard flint or the Marpesian cliff were standing there.” {Æneid 6,471} It was here Alexander the Great afterwards built gates and named them the “Caspian Gates” {= Sirdar Pass, near Derbent on the western shore of the Caspian Sea ~35 miles NE of Teheran}, which now the tribe of the Lazi guards as a Roman fortification. |

||||

| 51 | |||||

| Hic ergo certum tempus Amazones commanentes confortatæ sunt. | Here, then, the Amazons remained for some time and were much strengthened. | ||||

| Unde egressæ et Halym fluvium, qui juxta Gangram civitatem præterfluit, transeuntes, Armeniam, Syriam Ciliciamque, Galatiam, Pisidiam omniaque Asiæ loca æqua felicitate domuerunt ; Ioniam Eoliamque conversæ deditas sibi provincias effecerunt. | Then they departed and crossed the Halys (= Kisil-Irmák) river, which flows near the city of Çankiri {now Kiankari}, and with equal success subdued Armenia, Syria, Cilicia, Galatia, Pisidia and all the places of Asia Minor. Then they turned to Ionia and Æolia, and made provinces of them after their surrender. | ||||

| Ubi diutius dominantes etiam civitates castraque suo in nomine dicaverunt, Ephesi quoque templum Dianæ ob sagittandi ac venandi studium, quibus se artibus tradidissent, effusis opibus miræ pulchritudinis condiderunt. | Here they ruled for some time and even founded cities and camps bearing their name. At Ephesus also they built a very costly and beautiful temple for Diana, because of her delight in archery and the chase — arts to which they were themselves devoted. | ||||

| 52 | |||||

| Tali ergo in Scythia genitæ feminæ casu Asiæ regnis potitæ, per centum pæne annos tenuerunt, et sic demum ad proprias socias in cautes Marpesias quas superius diximus repedaverunt, in montem scilicet Caucasi. | Then these Scythian-born women, who had by such a chance gained control over the kingdoms of Asia, held them for almost a hundred years, and at last retreated to their own kinsfolk in the Marpesian rocks I have mentioned above, namely the Caucasus mountains. | ||||

| Cujus montis quia facta iterum mentio est, non ab re arbitror ejus tractum situmque describere, quando maximam partem orbis noscitur circuire jugo continuo. | Inasmuch as I have twice mentioned this mountain range, I think it not out of place to describe its extent and situation, for, as is well known, it encompasses a major part of the earth with its continuous chain. | ||||

| 53 | |||||

| Is namque ab Indico mari surgens, qua meridiem respicit, sole vaporatus ardescit ; qua septentrioni patet, rigentibus ventis est obnoxius et pruinis. Mox in Syriam curvato angulo reflexus, licet amnium plurimos emittat, in Vasianensem tamen regionem Euphratem Tigrimque navigeros, ad opinionem maximam, perennium fontium copiosis fundit uberibus. | Beginning at the Indian Ocean, where it faces the south it is warm, giving off vapor in the sun; where it lies open to the north it is exposed to chill winds and frost. Then bending back into Syria with a curving turn, it not only sends forth many other streams but, in the opinion of most, from the plenteous breasts of its perennial springs it also pours out the navigable Euphrates and Tigris into the Vasianensian {= the Basilisené (in Armenia) of Ptolemæus 5,13,13?} region. | ||||

| Qui, amplexantes terras Syrorum, « Mesopotamiam » et appellari faciunt et videri, in sinum rubri maris fluenta deponentes. | These rivers surround the land of the Syrians and cause it to be called and to seem “Mesopotamia” {= lit., “Between-the-rivers Land”}. Their waters empty into the bosom of the Persian Gulf. | ||||

| 54 | |||||

| Tunc in boream revertens Scythicas terras jugum antefatum magnis flexibus pervagatur atque ibidem opinatissima flumina in Caspium mare profundens Araxem, Cyrum et Cambysem, continuatoque jugo ad Rhiphæos usque montes extenditur. | Then turning back to the north, the range I have spoken of passes with great windings through the Scythian lands. There {i.e., from the Armenian Highland in northeast Asia Minor} it sends forth very famous rivers into the Caspian Sea — the Aras, the Kur and the Jora. It goes on in continuous range all the way to the Central Russian Upland. | ||||

| Indeque Scythicis gentibus dorso suo terminum præbens ad Pontum usque descendit, consertisque collibus Histri quoque fluenta contingit, quo amne scissus dehiscens, in Scythia quoque « Taurus » vocatur. | Thence it descends from the north toward the Black Sea, furnishing a boundary to the Scythian tribes by its ridge, and even touches the waters of the Danube {= probably the Dniepr} with its interlinked hills. Being cut by this river, it divides, and in Scythia is named Taurus {the Tauric Chersonese, i.e., the Crimean Peninsula} also. | ||||

| 55 | |||||

| Talis ergo tantusque et pæne omnium montium maximus excelsas suas erigens summitates, naturali constructione præstat gentibus inexpugnanda munimina. | Such then is the great range, almost the mightiest of mountain chains, rearing aloft its summits and by its natural conformation supplying men with impregnable fortifications. | ||||

| Nam locatim recisus, qua, dirupto jugo, vallis hiatu patescit, nunc Caspiæ portas, nunc Armenias, nunc Cilicias, vel secundum locum qualis fuerit, facit — vix tamen plaustro meabilis, lateribus in altitudinem utrimque desectis — qui pro gentium varietate diverso vocabulo nuncupantur. | Here and there it divides where the ridge breaks apart and leaves a deep gap, thus forming now the Caspian Gates, and again the Armenian or the Cilician Gates, or of whatever name the place may be. Yet they are barely passable for a wagon, with the sides abruptly rising to great heights on both right and left. The range has different names among various peoples. | ||||

| Hunc enim Himaum, mox Propanisum Indus appellat ; Parthus primum Choatram, post Niphatem edicit ; Syrus et Armenius Taurum, Scytha Caucasum ac Rhiphæum, iterumque in fine Taurum cognominat ; aliæque complurimæ gentes huic jugo dedere vocabula. | The Indian calls it the Himalaya range here and there the Hindu Kush. The Parthian calls it first Choatras {= mountains of Assyria and Media} and afterward Niphates {part of the Taurus range in Armenia, now Ala-dagh}; the Syrian and Armenian call it Taurus; the Scythian names it Caucasus and Rhiphæus {= the Central Russian Uplands}, and at its end calls it Taurus again. Many other tribes have given names to the range. | ||||

| Et quia de ejus continuatione pauca libavimus, ad Amazones, unde devertimus, redeamus. | Now that we have devoted a few words to describing its extent, let us return to the subject of the Amazons whence we have digressed. | ||||

| VIII 56 |

|||||

| Quæ, veritæ ne earum proles raresceret, a vicinis gentibus concubitum petierunt, factis nundinis semel in anno, ita ut futuri temporis eodem die revertentibus in id ipsum, quicquid partus masculi edidissent, patri redderent, quicquid vero feminei sexus nasceretur, mater ad arma bellica erudiret — sive, ut quibusdam placet, editis maribus, novercali odio infantis miserandi fata rumpebant. | Fearing their race would fail, they sought sexual intercourse with neighboring tribes. They appointed a day for meeting once in every year, so that when they should return to the same place on that day in the following year each mother might give over to the father whatever male child she had borne, but should herself keep and train for warfare whatever children of the female sex were born. Or else, as some maintain, they exposed the males, destroying the life of the pitiable child with stepmotherly hatred. | ||||

| Ita apud illas detestabile puerperium erat, quod ubique constat esse votivum. | Among them bearing a son was detested, though everywhere else it is desired. | ||||

| 57 | |||||

| Quæ crudelitas illis terrorem maximum cumulabat opinionis vulgatæ. ¿ Nam quæ, rogo, spes esset capto, ubi indulgeri vel filio nefas habebatur? | The terror of their cruelty was increased by common rumor; for what hope, pray, would there be for a captive, when it was considered wrong to spare even a son? | ||||

| Contra has, ut fertur, pugnavit Hercules, et Menalippen pæne plus dole quam virtute subegit. | Hercules, they say, fought against them and overcame Menalippe, yet almost more by guile than by valor. | ||||

| Theseus vero Hippolyten in præda tulit, de qua et genuit Hippolytum. | Theseus moreover, took Hippolyte captive, and of her he begat Hippolytus. | ||||

| Hæ quoque Amazones posthæc habuere reginam nomine Penthesileam, cujus Trojano bello exstant clarissima documenta. | And in later times the Amazons had a queen named Penthesilea, famed in the tales of the Trojan war. | ||||

| Nam hæ feminæ usque ad Alexandrum Magnum referuntur tenuisse regimen. | These women are said to have kept their power even to the time of Alexander the Great. | ||||

| IX 58 |

|||||

| Sed ne dicas : « De viris Gothorum sermo assumptus, ¿ cur in feminis tamdiu perseverat ? » | But say not “Why does a story which deals with the men of the Goths have so much to say of their women?” | ||||

| Audi et virorum insignem et laudabilem fortitudinem. | Hear, then, the tale of the famous and glorious valor of the men. | ||||

| Dio historicus et antiquitatum diligentissimus inquisitor, qui operi suo « Getica » titulum dedit (quos Getas jam superiore loco Gothos esse probavimus, Orosio Paulo dicente) — hic Dio regem illis post tempora multa commemorat nomine Telephum. | Now Dio, the historian and diligent investigator of ancient times, who gave to his work the title “Getica” (and the Getæ we have proved in a previous passage to be Goths {cf. 5,40 & 44, above}, on the testimony of Orosius Paulus) — this Dio, I say, makes mention of a later king of theirs named Telephus. | ||||

| Ne vero quis dicat hoc nomen a lingua Gothica omnino peregrinum esse, qui nescit animadvertat usu pleraque nomina gentes amplecti, ut Romani Macedonum, Græci Romanorum, Sarmatæ Germanorum, Gothi plerumque mutuantur Hunnorum. | Lest anyone say that this name is quite foreign to the Gothic tongue, let the ignorant find fault with the fact that the tribes of men make use of many names, even as the Romans borrow from the Macedonians, the Greeks from the Romans, the Sarmatians from the Germans, and the Goths frequently from the Huns. | ||||

| 59 | |||||

| Is ergo Telephus, Herculis filius natus ex Auge, sorori Priami conjugio copulatus, procerus quidem corpore, sed plus vigore terribilis, qui, paternam fortitudinem propriis virtutibus æquans, Herculis genitum formæ quoque similitudine referebat. Hujus itaque regnum « Mœsiam » appellavere majores. | This Telephus, then, a son of Hercules by Auge, and the husband of a sister of Priam, was of towering stature and terrible strength. He matched his father’s valor by virtues of his own and also recalled his sonship of Hercules by his likeness in appearance. Our ancestors called his kingdom “Mœsia.” | ||||

| Quæ provincia habet ab oriente ostia fluminis Danubii, a meridie Macedoniam, ab occasu Histriam, a septentrione Danubium. | This province has on the east the mouths of the Danube, on the south Macedonia, on the west Histria and on the north the Danube. | ||||

| 60 | |||||