|

|

German »Hermann«

(i.e., Siegfried) Monument,

Detmold, Germany |

The genetic and cultural foundations of the Germanic folk were laid in the period 2000-1500 B.C., when a tall, long-skulled (“dolichocephalic”) Indogermanic people from southern Russia with horses and war chariots invaded and mixed with a broad-skulled (“brachycephalic”) agricultural people in northern Europe (who had built tombs out of large boulders or “megaliths”) and imposed their language on it. The region covered by this new blend of two peoples - the original Germanic homeland of southern Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany (Schleswig-Holstein and eastern Lower Saxony) - remained fairly well isolated from the rest of the world during the following millennium (1500-550 B.C.). Such conditions saw the development of a hardy stock of reddish-blond, blue-eyed farmers, whose adult males averaged five feet eight inches in height and about one third of whose females died in childbirth. Average lifespan was about thirty-seven years. They spoke Proto-Germanic (early Germanic), a primarily Indogermanic dialect with a large number of words from the pre-Indogermanic, Megalithic culture. The earliest archeologically identifiable Germanic culture (ca. 550 B.C.) of this new people is found in the area of Jastorf, a town about 100 km/60 miles southeast of modern Hamburg, whence it spread (550-250 B.C.) to the rest of the Germanic-speaking people.

By the time of Caesar Augustus, (30 B.C.-A.D. 14), they had pushed eastward to the Vistula (modern Poland). The south of modern Germany had remained Celtic up to that time. As they expanded, the early Germanics began to split up into various cultural and linguistic divisions: the North Germans (Scandinavia), North-Sea Germans (Friesland to Jutland), Rhein-Weser Germans (also called “West Germans”), the Elbe Germans (throughout the drainage area of the Elbe river) and the Oder-and-Vistula Germans in the east. The Roman authors Plinius and Tacitus tell us that they knew of three cult groupings in the west (the Ingwaeons, Istwaeons and Herminons), all of whom believed themselves to be descended from a common ancestor, Mannus (“man”).

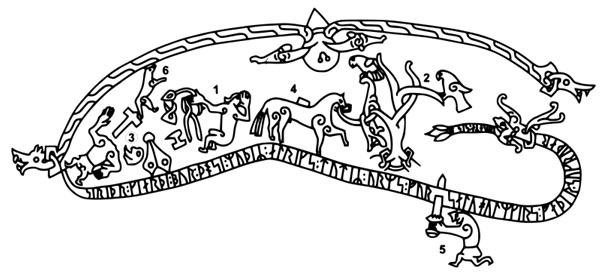

The written history of the Germanic peoples began with their violent contacts with Rome. The Khimbrians (Cimbri) and the Teutons (Teutones) erupted into the Roman sphere of influence in the areas of modern Austria, Switzerland, southern France and northern Italy around 100 B.C. Within a few years they were annihilated by the far more disciplined and organized Roman forces, but not before some of them had learned the alphabet used in northern Italy (the so-called “North Etruscan”) and taken it to the north to use as runes - a kind of ancient tarot.

Over the next century the Romans spread northwards to conquer all of Gaul (modern France), but their expansion into the Germanic areas east of the Rhein river was permanently checked in A.D. 9, when a great Germanic military genius, Arminius, slaughtered an entire Roman army consisting of three legions and their logistical support units. In the words of the Roman historian Tacitus, he was the “Liberator of Germany.”

The pre-literate historical traditions of the Germans

|

German »Hermann«

(i.e., Siegfried) Monument,

New Ulm, Minnesota, U.S.A. |

Many of the great Germanic epics and songs (the Old Icelandic Eddas, the Nibelungenlied and various myths) of great antiquity center around a key figure known as Siegfried (literally, “Victorious Peace”), also known as Sigfrid and, in Old Norse, Sigurd. In the nineteenth century, the great German composer Richard Wagner wrote a series of famous operas entitled “Der Ring des Nibelungen,” which centers on the legendary hero Siegfried. The tradition, now mostly literary, continues to this day. For centuries, scholars have puzzled over what historical character might have generated this wealth of legends and songs. In the third quarter of the twentieth century, the researchers finally determined exactly who this individual was: Arminius.

Arminius and the Destruction of Varus

Arminius (also written Armenius; the name is probably Latin in origin, and recorded thus only in the Latin and Greek records of the time) was a Cheruskan prince born about 16 B.C. and treacherously poisoned to death by his in-laws about A.D. 21. He may have obtained the name “Armenius” (likely the proper spelling) after “armenium,” a vivid blue, ultramarine pigment made from a stone from Armenia, due to his piercing blue eyes, a feature which many among the Germanic peoples have to this day. (Several centuries ago early scholars mistakenly thought “Arminius” was a Latinized form of the German “Hermann,” and referred to him thus in their literary productions.) His brother's Latin name was Flavus (“the Blond”), which is also a name based on physical characteristics. The name of his father, a prince of the Cheruskan tribe, was Sigimer (“Victory-renowned”), and his father-in-law (who had tried to betray him to the Romans and later kidnapped his pregnant daughter, Arminius’ wife, and gave her to the Romans as a captive) was Segestes. While Seg-/Sig- meant “victory/victorious” (cf. modern German Sieg), the second element of the father’s name, -mēr, meant “famous” (cf. Visigothic mēr- “speaking about; spoken about”), and the ending -st- of the father-in-law’s name may be a superlative ending, so that the latter name could mean “Most Victorious.”

Given the Proto-Germanic custom of giving children names containing at least one element found in the parent’s name, it is thus most probable that Arminius’ original name began with Seg-/Sig-. It is found, for instance, in the epics of later Germanic languages such as the Nibelungenlied and the Völsunga saga, in which the dragon-slaying hero is respectively called Sigfrid (= Pgmc. *Sigifriðaz) and Sigurðr (= Pgmc. *Sigiwarðaz). The Old English form of this latter name was Sigeweard. As for the second elements: *friþ/*frið = “peace,” and *warð = “safeguard.” In general, Nordic literature seems to have been more conservative than the southern Germanic (German) tradition, hence it is more likely that the name was originally “Sigiwarðaz.”

His wife, Thusnelda (Þūsnildo, perhaps “Powerful Beauty”), had originally been promised by her father Segestes, also a Cheruskan prince, to a different man, but she ran away to marry Arminius. Segestes, whose paternal and princely rights and pride had thus been violated, and who had already opposed Arminius, thereupon became his permanent and deadly archfoe. Thusnelda's son with Arminius-Sigiwarðus was born after she had been kidnapped by her father and delivered captive to the Romans; she gave her son the name Thumelicus (Þūmēlika "Powerful Kindness"), which alliterated with her own name.

Arminius had been sent to Rome for early military training, spoke excellent Latin, possessed Roman citizenship and held the rank of Roman knight. He seems to have commanded a regular Cheruskan auxiliary squadron in Roman service, at first during the Pannonian (Balkan) revolt of A.D. 7-8, and thereafter in Germany.

In Germany a rebellion began - originally probably as a revolt of the troops. But it was aggravated and spread by Arminius through a coalition of the Cheruskans and neighboring tribes.

In September of A.D. 9, he drew three Roman legions (the 17th, 18th and 19th) commanded by Quintilius Varus deep into the narrow defile called the Teutoburgiensis saltus between steep, forested hillsides and deep swamps, and annihilated them. This success transformed him into the most famous figure of all early Germanic history.

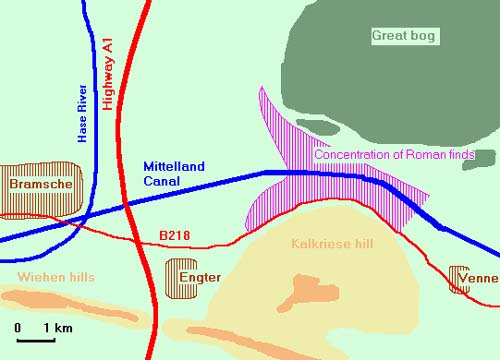

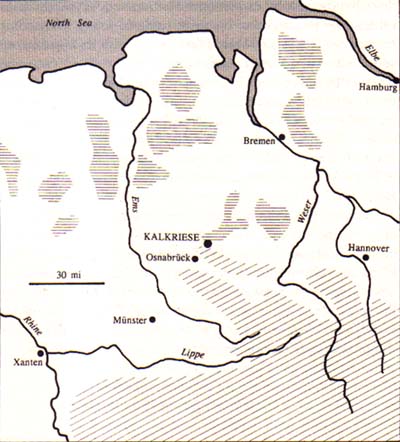

There has been considerable dispute as to the actual whereabouts of the Teutoburgiensis saltus. One of the candidates suggested in recent years is at the foot of Kalkriese Hill in Osnabrück County (Kreis), as depicted below.

Kalkriese Mountain (ancient Teuton Mountain) Pass,

one of the locations proposed

as the site of the slaughter of Varus and his legions

by the Cheruskan prince Sigiwarðus,

the Siegfried of Germanic legend

and Arminius of Roman history

Location of Kalkriese Mountain

(a suggested possibility for the Teutoburg

of antiquity) in northern Germany

The later punitive expedition (A.D. 14-16) of the Roman general Germanicus had great trouble in invading Germany even with eight legions, and was unable to reestablish Roman rule there. This effectively terminated Rome's attempts to expand into Germany east of the Rhein.

Arminius first attempted to win over Marbod, king of the Frontiersmen (“Men of the Marches,” Marcomanni, ancestors of the Bavarians) but, failing this, attacked and defeated him. Finally, in A.D. 19, the great Germanic general was undone by a revolt of the nobility and murdered (apparently poisoned) by his in-laws, who were loyal to his wife's father, Segestes.

Of Arminius, the Roman historian Tacitus wrote, “He was undoubtedly the liberator of Germany, a man who did not, as did other kings and generals, challenge Rome in its early stages, but when it stood at the zenith of its power. In battles he fought with varying success, but in the war he remained unconquered. His deeds live on in the songs of his people....” (Tacitus, Annals, 1, 57,58)

These songs were handed down through the generations, and the story of Arminius became transformed into myth in the process.

The Correspondences between Arminius and Siegfried

Famous twentieth-century researchers such as the University of Bonn's classical philologist Ernst Bickel and the Viennese specialist in the Old Norse Eddas, Otto Höfler, retraced the development of these epic poems and discovered that their hero, Siegfried, is indeed the figure whose Latin name has come down to us as Arminius.

As explained in S. Fischer-Fabian's book, Die ersten Deutschen: Über das rätselhafte Volk der Germanen (Bergisch Gladbach: Verlagsgruppe Lübbe GmbH & Co. KG, 1975, 2003), pp. 328f., these researchers have extracted a series of striking correspondences, among them the following:

- Siegfried was murdered by his wife's relatives - as was Arminius, since the propinqui (“kin”) of Tacitus can only mean the clan of his father-in-law, Segestes.

- Siegfried slew a dragon (Fáfnir), but so also did Arminius, for whom the “dragon” was the serpentine, 20-kilometer-long, Roman army column.

- Siegfried grew up in Xanten on the lower Rhein: Xanten was the location of the location of the ancient Roman Castra Vetera (“Old Camp”), the powerful Roman stronghold to which the remnants of Varus' army had fled after the debacle;

- Siegfried was suckled by a doe and died like a deer pursued by hunters: Arminius belonged to the tribe of the Cheruskans, a name derived from the Germanic word-stem herut “deer, hart.” (In Latin, “ch” was the spelling used to render the Germanic voiceless palatal and velar fricatives, which sounded like the “ch” in modern German “Chemie” or the “g” in Spanish “gente.” Cf. the mead-hall named heorot or “Hart's Hall,” in the Old English epic, Beowulf. This word is also the ancestor of modern English hart.)

- Siegfried was the son of the king Sigemund, while Arminius' father was called Sigimer (Latin form: Segimer).

- Siegfried fought with the dragon on the Gnitaheiðr (the Rocky Heath or “rock-strewn, gravelly plain” - cf. New Norwegian gnita “broken piece, shard” and Swedish dialectal , gnitu, “crumb, particle”), while Arminius defeated the Romans on the Gnidderhöi, the Knetterheide (Knetter Heath) in the vicinity of Schötmar southeast of Herford (which itself is northeast of Bielefeld in northwestern Germany), suspected of being one of the locations where the three-day battle with Varus took place.

This series of parallels cannot be mere coincidence. The researchers' arguments are brilliant in their logic and absolutely convincing. Although all of these arguments’ details cannot be set forth here, the important thing is that they have converted what was formerly a hypothesis into a fact: Arminius was Siegfried. |

|

|

Face of German “Hermann” (Siegfried),

Detmold, Germany |

Face of American “Hermann” (Siegfried),

New Ulm, Minnesota |

APPENDIX

The Etymology of “Teutoburg”

|

A critical point is the meaning of the topographical name, “saltus Teutoburgiensis,” traditionally translated as “Teutoburg forest” (in German, “Teutoburger Wald”). It referred to a narrow stretch of land in which the historical battle is reported as having taken place. An analysis of this name can contribute to narrowing the selection of possible locations of the battlefield.

To begin with, the fourth-declension Latin “saltus” serves as the form of two different words:

- #1 saltus (Genitive saltūs)

- “leap, spring, jump” — derived from the verb salīre “to leap, jump; gush, spurt”;

- #2 saltus (Genitive saltūs)

- “narrow forest pathway, forested gulch, rough hill country partly or completely covered with forest or bush.” This is a homonym of #1 but is of independent origin, being related via Indogermanic ancestry to Greek ἄλσος (“a glade or grove” — Liddell & Scott) and the Elean-Greek dialectal form Ἄλτις (“grove of Zeus at Olympia”; Elea was a Greek colony on the west coast of southern Italy, known in Latin as Velia).

|

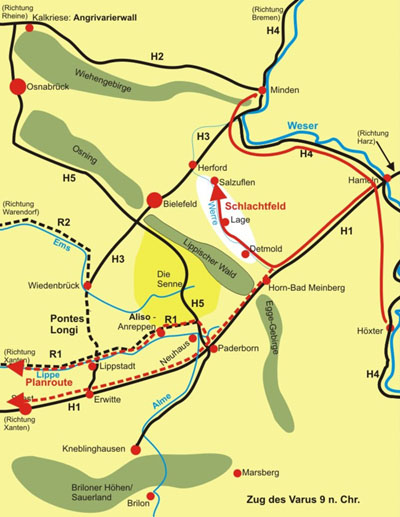

Teutoburg battle: Route taken by Varus

“Schlachtfeld” = battlefield |

Moreover a German researcher, Prof. Dr. Siegfried G. Schoppe (http://www.arminius-varusschlacht.de/), presents the following argument: the Latin word “saltus” in Saltus Teutoburgiensis did not originally mean, as usually assumed, either “leap” (#1) or “rugged forested terrain” (#2). Rather, this particular saltus comes from a hydronym (waterway-name) which, like Ems (Amisia), Lippe (Lupia) or Rhine (Rhenus), was taken over by the Romans; today as then, this river, the Salze (earlier Salz, Proto-Germanic Salt ), flows into the Werre river at the town of Salzuflen. Since in Latin all river names were masculine (with a nominative singular ending in -us), this Germanic river name was Latinized as Saltus (a second-declension proper noun with a genitive Saltī ). Thus there was

- #3 Saltus (Genitive Saltī )

- The Salt river

Later, the similarity in form with saltus #2 led to a confusion of the two words, and in the minds of later Roman historians the name for the Salt river became fused with the common noun saltus #2 for “rugged forested terrain” and was transferred into the fourth declension (genitive -ūs). But the area actually referred to by saltus #3 — as the range in which the battle of attrition took place — is the Werre Valley between Detmold and Salzuflen.

As for the word “Teutoburg,” the general consensus of Germanic philologists is that the Germanic “*burg” meant a population center, usually fortified, and usually on a height. Cf. the Gothic baúrgs “castle, citadel; (open or fortified) city,” baúrgja, “citizen, burgher,” baúrgs-waddjus “town wall, city circumvallation” and the like. It is related to German Berg “mountain”. Towns and cities in Gallia and Germania, as in many other lands, were typically walled and located on heights to make them more difficult of attack. Similarly, Old High German burg, burgh, burc(h), burk, bureg, buruc, purg and purch all meant “city” or “town,” particularly such as were located atop hills, natural or artificial, or other high places of various sorts, and surrounded by palisades and ditches for protection.

In early Proto-Germanic, the sound represented by the letter /g/ was a velar or palatal fricative, sounding much like the “g” in Spanish agua (“water”). This made it easily changed by its phonetic environment. Thus Proto-Germanic “*burg” later gave rise to such different English words as bury (“make a mound” [over something interred]), burrow (cause the earth to rise over a tunnel, as moles do), and the suffixes -bury, -burgh and -borough (originally indicating hilltop towns). In Anglo-Saxon (early Old English), the y/w alternation found in these words appears today in words such as day/dawn, lay/law/lawn (“that which has been laid down”), say/(the old) saw, and even buy/bow (“buying” was done by those with gold or metal arm rings or coils which were bent off and given in lieu of currency), dray/draw.

*burg was the Proto-Germanic equivalent of the Celtic *dūn (pronounced “doon”) seen in Latin toponyms such as Lugdūnum (modern Lyons), Cæsarodūnum (Tours), Augustodūnum (Autun), Verodūnum (Verdun), et cetera. The Celtic term was imported into West Germanic, where the “d” became “t” in the First Sound Shift (around or before 500 B.C.). In the Second, or High German, Sound Shift (which separated English and German, ca. A.D. 700), the “t” further changed to “ts” (today spelled “z”) at the beginning of a word-stem or in certain other places (cf. English salt vs. German Salz). The modern English descendant of “dun” is town and its corresponding (unaccented) suffix -ton; the modern German descendant is Zaun “fence” — originally, “fortification” (an echo of the palisade surrounding most early towns). Likewise the purely Germanic word corresponding to “fortified hilltop town,” that is, “burg,” was also retained for “town,” and hence we have “borough.”

Finally, the “Teuto-” in “Teutoburg” can only refer to the Teutons who, with the allied tribe of the Cimbri, invaded the Roman sphere in 113 B.C. and were wiped out by Marius in 102 B.C. near Aquæ Sextiæ. Presumably the heights of Teutoburg hill, with water at its base, would have served as a suitable spot for an encampment or town populated by the Teutons before their trek to the south, and the location preserved their name for over a century afterwards.

Thus in the ancient time before the spread of low-lying towns in the north, “Teuto-burg” must have meant “Teuton Hilltop-Town,” or more simply “Town of the Teutons.” In combination with the Latin “saltus” #2 “forested uplands”, or Latinized-Germanic “saltus” #3 “the Salt River,” “saltus Teutoburgiensis” meant either “the partly forested defile at the foot of Teuton Town Heights” or, more probably, “the Salt River lowlands below Teuton Town.”

|

|

|

|

|

Gajus Vellejus Paterculus

HISTORIA ROMANA 117,1 — 119,5 |

| |

| CAPUT CXVII |

| 1 |

| Tantum quod ultimam imposuerat Pannonico ac Delmatico bello Cæsar manum, quum intra quinque consummati tanti operis dies funestæ ex Germania epistulæ nuntium attulere cæsi Vari trucidatarumque legionum trium totidemque alarum et sex cohortium, velut in hoc saltem tantummodo indulgente nobis fortuna, ne occupato duce tanta clades inferretur. Sed et causa et persona moram exigit. |

Scarcely had [Tiberius] Caesar put the finishing touch upon the Pannonian and Dalmatian war, when, within five days of the completion of this task, dispatches from Germany brought the baleful news of the death of Varus, and of the slaughter of three legions, of as many divisions of cavalry, and of six cohorts — as though fortune were granting us this indulgence at least, that such a disaster should not be brought upon us when our commander was occupied by other wars. The cause of this defeat and the personality of the general require of me a brief digression. |

| 2 |

| Varus Quintilius, illustri magis quam nobili ortus familia, vir ingenio mitis, moribus quietus, ut corpore ita animo immobilior, otio magis castrorum quam bellicæ adsuetus militiæ, pecuniæ vero quam non contemptor, Syria, cui præfuerat, declaravit — quam pauper divitem ingressus, dives pauperem reliquit. |

Varus Quintilius, descended from a famous rather than a high-born family, was a man of mild character and of a quiet disposition, somewhat slow in mind as he was in body, and more accustomed to the leisure of the camp than to actual service in war. That he was no despiser of money is demonstrated by his governorship of Syria: he entered the rich province a poor man, but left it a rich man and the province poor. |

| 3 |

| Is quum exercitui, qui erat in Germania, præesset, concepit esse homines qui nihil præter vocem membraque haberent hominum, quique gladiis domari non poterant, posse jure mulceri. |

When placed in charge of the army in Germany, he entertained the notion that the Germans were a people who were men only in limbs and voice, and that they, who could not be subdued by the sword, could be soothed by the law. |

| 4 |

| Quo proposito mediam ingressus Germaniam, velut inter viros pacis gaudentes dulcedine, jurisdictionibus agendoque pro tribunali ordine, trahebat æstiva. |

With this purpose in mind he entered the heart of Germany as though he were going among a people enjoying the blessings of peace, and sitting on his tribunal he wasted the time of a summer campaign in holding court and observing the proper details of legal procedure. |

| |

| CAPUT CXVIII |

| 1 |

| At illi — quod nisi expertus vix credat — in summa feritate versutissimi, natumque mendacio genus, simulantes fictas litium series et nunc provocantes alter alterum in jurgia, nunc agentes gratias quod ea Romana justitia finiret feritasque sua novitate incognitæ disciplinæ mitesceret et solita armis discerni jure terminarentur, in summam socordiam perduxere Quintilium, usque eo ut se prætorem urbanum in foro jus dicere, non in mediis Germaniæ finibus exercitui præesse crederet. |

But the Germans, who with their great ferocity combine great craft, to an extent scarcely credible to one who has had no experience with them, and are a race to lying born, by trumping up a series of fictitious lawsuits, now provoking one another to disputes, and now expressing their gratitude that Roman justice was settling these disputes, that their own barbarous nature was being softened down by this new and hitherto unknown method, and that quarrels which were usually settled by arms were now being ended by law, brought Quintilius to such a complete degree of negligence, that he came to look upon himself as a city praetor administering justice in the forum, and not a general in command of an army in the heart of Germany. |

| 2 |

| Tum juvenis genere nobilis, manu fortis, sensu celer, ultra barbarum promptus ingenio, nomine Arminius, Sigimeri principis gentis ejus filius, ardorem animi vultu oculis præferens, assiduus militiæ nostræ prioris comes, jure etiam civitatis Romanæ decus equestris consecutus gradus, segnitia ducis in occasionem sceleris usus est, haud imprudenter speculatus neminem celerius opprimi, quam qui nihil timeret, et frequentissimum initium esse calamitatis securitatem. |

Thereupon appeared a young man of noble birth, brave in action and alert in mind, possessing an intelligence quite beyond the ordinary barbarian; he was, namely, Arminius, the son of Sigimer, a prince of that nation, and he showed in his countenance and in his eyes the fire of the mind within. He had been associated with us constantly on private campaigns, and had even attained the dignity of equestrian rank. This young man made use of the negligence of the general as an opportunity for treachery, sagaciously seeing that no one could be more quickly overpowered than the man who feared nothing, and that the most common beginning of disaster was a sense of security. |

| 3 |

| Primo igitur paucos, mox plures in societatem consilii recepti; opprimi posse Romanos et dicit et persuadet, decretis facta jungit, tempus insidiarum constituit. |

At first, then, he admitted but a few, later a large number, to a share in his design; he told them, and convinced them too, that the Romans could be crushed, added execution to resolve, and named a day for carrying out the plot. |

| 4 |

| Id Varo per virum ejus gentis fidelum clarique nominis, Segesten, indicatur. Postulabat etiam vinciri socios. Sed prævalebant jam fata consiliis omnemque animi ejus aciem præstrinxerant: quippe ita se res habet, ut plerumque cujus fortunam mutaturus est deus, consilia corrumpat efficiatque — quod miserrimum est — ut quod accidit etiam merito accidisse videatur, et casus in culpam transeat. Negat itaque se credere; speciemque in se benevolentiæ ex merito æstimare profitetur. Nec diutius post primum indicem secundo relictus locus. |

This was disclosed to Varus through Segestes, a loyal man of that race and of illustrious name, who also demanded that the conspirators be put in chains. But fate now dominated the plans of Varus and had blindfolded the eyes of his mind. Indeed, it is usually the case that heaven perverts the judgement of the man whose fortune it means to reverse, and brings it to pass — and this is the wretched part of it — that that which happens by chance seems to be deserved, and accident passes over into culpability. And so Quintilius refused to believe the story, and insisted upon judging the apparent friendship of the Germans toward him by the standard of his merit. And, after this first warning, there was no time left for a second. |

| |

| CAPUT CXIX |

| 1 |

| Ordinem atrocissimæ calamitatis qua nulla — post Crassi in Parthis damnum — in externis gentibus gravior Romanis fuit, justis voluminibus, ut alii ita nos, conabimur exponere: nunc summa deflenda est. |

The details of this terrible calamity, the heaviest that had befallen the Romans on foreign soil since the disaster of Crassus in Parthia, I shall endeavour to set forth, as others have done, in my larger work. Here I can merely lament the disaster as a whole. |

| 2 |

| Exercitus omnium fortissimus, disciplina, manu experientiaque bellorum inter Romanos milites princeps, marcore ducis, perfidia hostis, iniquitate fortunæ circumventus, quum ne pugnandi quidem egrediendive occasio nisi inique, nec in quantum voluerant, data esset immunis — castigatis etiam quibusdam gravi pœna, quia Romanis et armis et animis usi fuissent — inclusus silvis, paludibus, insidiis ab eo hoste ad internecionem trucidatus est, quem ita semper more pecudum trucidaverat, ut vitam aut mortem ejus nunc ira, nunc venia temperaret. |

An army unexcelled in bravery, the first of Roman armies in discipline, in energy, and in experience in the field, through the negligence of its general, the perfidy of the enemy, and the unkindness of fortune was surrounded, nor was as much opportunity as they had wished given to the soldiers either of fighting or of extricating themselves, except against heavy odds; nay, some were even heavily chastised for using the arms and showing the spirit of Romans. Hemmed in by forests and marshes and ambuscades, it was exterminated almost to a man by the very enemy whom it had always slaughtered like cattle, whose life or death had depended solely upon the wrath or the pity of the Romans. |

| 3 |

| Duci plus ad moriendum quam ad pugnandum animi fuit: quippe paterni avitique successor exempli se ipse transfixit. |

The general had more courage to die than to fight, for, following the example of his father and grandfather, he ran himself through with his sword. |

| 4 |

| At e præfectis castrorum duobus, quam clarum exemplum L. Eggius tam turpe Cejonius prodidit: qui, quum longe maximam partem absumpsisset acies, auctor deditionis supplicio quam prœlio mori maluit. At Vala Numonius, legatus Vari, cetera quietus ac probus, diri auctor exempli, spoliatum equite peditem relinquens fuga cum alis Rhenum petere ingressus est. Quod factum ejus fortuna ulta est; non enim desertis superfuit, sed desertor occidit. |

Of the two prefects of the camp, Lucius Eggius furnished a precedent as noble as that of Ceionius was base, who, after the greater part of the army had perished, proposed its surrender, preferring to die by torture at the hands of the enemy than in battle. Vala Numonius, lieutenant of Varus, who, in the rest of his life, had been an inoffensive and an honourable man, also set a fearful example in that he left the infantry unprotected by the cavalry and in flight tried to reach the Rhine with his squadrons of horse. But fortune avenged his act, for he did not survive those whom he had abandoned, but died in the act of deserting them. |

| 5 |

| Vari corpus semiustum hostilis laceraverat feritas; caput ejus abscisum latumque ad Marboduum et ab eo missum ad Cæsarem, gentilicii tamen tumuli sepultura honoratum est. |

The body of Varus, partially burned, was mangled by the enemy in their barbarity; his head was cut off and taken to Maroboduus and was sent by him to Caesar; but in spite of the disaster it was honoured by burial in the tomb of his family. |

|

Publius Cornelius Tacitus

Annales 60,1 — 62,2 |

| |

| CAPUT LX |

| 1 |

| Conciti per hæc non modo Cherusci, sed conterminæ gentes, tractusque in partis Inguiomerus Arminii patruus, vetere apud Romanos auctoritate; unde major Cæsari metus. |

This language roused not only the Cherusci but the neighboring tribes and drew to their side Ingwiomer, the uncle of Arminius, who had long been respected by the Romans. This increased Caesar’s alarm. |

| 2 |

| Et ne bellum mole una ingrueret, Cæcinam cum quadraginta cohortibus Romanis distrahendo hosti per Bructeros ad flumen Amisiam mittit, equitem Pedo præfectus finibus Frisiorum ducit. Ipse impositas navibus quattuor legiones per lacus vexit; simulque pedes, eques, classis apud prædictum amnem convenere. Chauci quum auxilia pollicerentur, in commilitium asciti sunt. |

That the war might not burst in all its fury on one point, he sent Cæcina through the Bructeri to the river Amisia with forty Roman cohorts to distract the enemy, while the cavalry was led by its commander Pedo by the territories of the Frisii. Germanicus himself put four legions on shipboard and conveyed them through the lakes, and the infantry, cavalry, and fleet met simultaneously at the river already mentioned. The Chauci, on promising aid, were associated with us in military fellowship. |

| 3 |

| Bructeros sua urentes expedita cum manu L. Stertinius missu Germanici fudit; interque cædem et prædam repperit undevicesimæ aquilam cum Varo amissam. Ductum inde agmen ad ultiomos Bructerorum, quantumque Amisiam et Lupiam amnes inter, vastatum, haud procul Teutoburgiensi saltu, in quo reliquiæ Vari legionumque insepultæ dicebantur. |

Lucius Stertinius was despatched by Germanicus with a flying column and routed the Bructeri as they were burning their possessions, and amid the carnage and plunder, found the eagle of the nineteenth legion which had been lost with Varus. The troops were then marched to the furthest frontier of the Bructeri, and all the country between the rivers Ems and Lippe was ravaged, not far from the forest of Teutoburg where the remains of Varus and his legions were said to lie unburied. |

| CAPUT LXI |

| 1 |

| Igitur cupido Cæsarem invadit solvendi suprema militibus ducique, permoto ad miserationem omni qui aderat exercitu ob propinquos, amicos, denique ob casus bellorum et sortem hominum. Præmisso Cæcina ut occulta saltuum scrutaretur pontesque et aggeres umido paludum et fallacibus campis imponeret, incedunt mæstos locos visuque ac memoria deformes. |

Germanicus upon this was seized with an eager longing to pay the last honor to those soldiers and their general, while the whole army present was moved to compassion by the thought of their kinsfolk and friends, and, indeed, of the calamities of wars and the lot of mankind. Having sent on Cæcina in advance to reconnoiter the obscure forest-passes, and to raise bridges and causeways over watery swamps and treacherous plains, they visited the mournful scenes, with their horrible sights and associations. |

| 2 |

| Prima Vari castra lato ambitu et dimensis principiis trium legionum manus ostentabant; deinde semiruto vallo, humili fossa accisæ jam reliquiæ consedisse intellegebantur; medio campi albentia ossa, ut fugerant, ut restiterant, disjecta vel aggerata. |

Varus’s first camp with its wide circumference and the measurements of its central space clearly indicated the handiwork of three legions. Further on, the partially fallen rampart and the shallow fosse suggested the inference that it was a shattered remnant of the army which had there taken up a position. In the center of the field were the whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. |

| 3 |

| Adjacebant fragmina telorum equorumque artus, simul truncis arborum antefixa ora. Lucis propinqui barbaræ aræ, apud quas tibunos ac primorum ordinum centuriones mactaverant. |

Nearby lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees. In the adjacent groves were the barbarous altars, on which they had immolated tribunes and first-rank centurions. |

| 4 |

| Et cladis ejus superstites, pugnam aut vincula elapsi; referebant hic cecidisse legatos, illic raptas aquilas; primum ubi vulnus Varo adactum, ubi infelici dextera et suo ictu mortem invenerit; quo tribunali contionatus Arminius, quot patibula captivis, quæ scrobes, utque signis et aquilis per superbiam illuserit. |

Some survivors of the disaster who had escaped from the battle or from captivity, described how this was the spot where the officers fell, how yonder the eagles were captured, where Varus was pierced by his first wound, where too by the stroke of his own ill-starred hand he found for himself death. They pointed out too the raised ground from which Arminius had harangued his army, the number of gibbets for the captives, the pits for the living, and how in his exultation he insulted the standards and eagles. |

| CAPUT LXII |

| 1 |

| Igitur Romanus, qui aderat, exercitus sextum post cladis annum trium legionum ossa nullo noscente, alienas reliquias an suorum humo tegeret, omnes ut conjunctos, ut consanguineos aucta in hostem ira mæsti simul et infensi condebant. Primum extruendo tumulo cæspitem Cæsar posuit, gratissimo munere in defunctos et præsentibus doloris socius. |

And so the Roman army now on the spot, six years after the disaster, in grief and anger, began to bury the bones of the three legions, not a soldier knowing whether he was interring the relics of a relative or a stranger, but looking on all as kinsfolk and of their own blood, while their wrath rose higher than ever against the foe. In raising the barrow Caesar laid the first sod, rendering thus a most welcome honor to the dead, and sharing also in the sorrow of those present. |

| 2 |

| Quod Tiberio haud probatum, seu cuncta Germanici in deterius trahenti, sive exercitum imagine cæsorum insepultorumque tardatum ad prœlia et formidolosiorem hostium credebat; neque imperatorem auguratu et vetustissimis cærimoniis præditum attrectare feralia debuisse. |

This Tiberius did not approve, either interpreting unfavorably every act of Germanicus, or because he thought that the spectacle of the slain and unburied made the army slow to fight and more afraid of the enemy, and that a general invested with the augurate and its very ancient ceremonies ought not to have polluted himself with funeral rites. |

|

Lucius Annæus Florus

The Epitome of Roman History, Book 2 |

| |

| Chapter 30. The German War, 21—39 |

| 21 |

| Germaniam quoque utinam vincere tanti non putasset! Magis turpiter amissa est quam gloriose adquisita. |

It could be wished that Cæsar had not set such store on conquering Germany also. Its loss was a disgrace which far outweighed the glory of its acquisition. |

| 22 |

| Sed quatenus sciebat patrem suum C. Cæsarem bis transvectum ponte Rhenum quæsisse bellum, in illius honorem concupierat facere provinciam; et factum erat, si barbari tam vitia nostra quam imperia ferre potuissent. |

But since he was well aware that his father, Gaius Cæsar, had twice crossed the Rhine by bridging it and sought hostilities against Germany, he had conceived the desire of making it into a province to do him honour. His object would have been achieved if the barbarians could have tolerated our vices as well as they tolerated our rule. |

| 23 |

| Missus in eam provinciam Drusus primos domuit Usipetes, inde Tencteros percurrit et Catthos. Nam Marcomannorum spoliis et insignibus quendam editum tumulum in tropæi modum excoluit. |

Drusus was sent into the province and conquered the Usipetes first, and then overran the territory of the Tencturi and Catthi. He erected, by way of a trophy, a high mound adorned with the spoils and decorations of the Marcomanni. |

| 24 |

| Inde validissimas nationes Cheruscos Suebosque et Sicambros pariter adgressus est, qui viginti centurionibus in crucem actis hoc velut sacramento sumpserant bellum, adeo certa victoriæ spe, ut prædam in antecessum pactione diviserint. Cherusci equos, |

Next he attacked simultaneously those powerful tribes, the Cherusci, Suebi and Sicambri, who had begun hostilities after crucifying twenty of our centurions, an act which served as an oath binding them together, and with such confidence of victory that they made an agreement in anticipation for dividing the spoils. The Cherusci had chosen the horses, |

| 25 |

| Suebi aurum et argentum, Sicambri captivos elegerant; sed omnia retrorsum. Victor namque Drusus equos, pecora, torques eorum ipsosque prædam divisit et vendidit; |

the Suebi the gold and silver, the Sicambri the captives. Everything, however, turned out contrariwise; for Drusus, after defeating them, divided up their horses, their herds, their necklets and their own persons as spoil and sold them. |

| 26 |

| et præterea in tutelam provinciæ præsidia atque custodias ubique disposuit per Mosam flumen, per Albin, per Visurgin. In Rheni quidem ripa quinquaginta amplius castella direxit. Bonnam et Moguntiacum pontibus junxit castellisque firmavit. |

Furthermore, to secure the province he posted garrisons and guard-posts all along the Meuse, Elbe and Weser. Along the banks of the Rhine he disposed more than five hundred forts. He built bridges at Bonn and Mainz, and left forts to protect them. |

| 27 |

| Invisum atque inaccessum in id tempus Hercynium saltum patefecit. Ea denique in Germania pax erat, ut mutati homines, alia terra, cælum ipsum mitius molliusque solito videretur. |

He opened a way through the Hercynian forest, which had never before been visited or traversed. In a word, there was such peace in Germany that the inhabitants seemed changed, the face of the country transformed, and the very climate milder and softer than it used to be. |

| 28 |

| Denique non per adulationem, sed ex meritis, defuncto ibi fortissimo juvene, ipse, quod numquam alias, senatus cognomen ex provincia dedit. |

Lastly, when the gallant young general had died there, the senate itself, not from flattery but as an acknowledgment of his merit, did him the unparalleled honour of bestowing upon him a surname derived from the name of a province. |

| 29 |

| Sed difficilius est provincias obtinere quam facere; viribus parantur, jure retinentur. |

But it is more difficult to retain than to create provinces; they are won by force, they are secured by justice. |

| 30 |

| Igitur breve id gaudium. Quippe Germani victi magis quam domiti erant, moresque nostros magis quam arma sub imperatore Druso suspiciebant; |

Therefore our joy was short-lived; for the Germans had been defeated rather than subdued, and under the rule of Drusus they respected our moral qualities rather than our arms. |

| 31 |

| postquam ille defunctus est, Vari Quinctilii libidinem ac superbiam haud secus quam sævitiam odisse cœperunt. Ausus ille agere conventum, et in Catthos edixerat, quasi violentiam barbarorum lictoris virgis et præconis voce posset inhibere. |

After his death they began to detest the licentiousness and pride not less than the cruelty of Quinctilius Varus. He had the temerity to hold an assembly and had issued an edict against the Catthi, just as though he could restrain the violence of barbarians by the rod of a lictor and the proclamation of a herald. |

| 32 |

| At illi, qui jam pridem robigine obsitos enses inertesque mærerent equos, ut primum togas et sæviora armis jura viderunt, duce Armenio arma corripiunt; |

But the Germans who had long been regretting that their swords were rusted and their horses idle, as soon as they saw the toga and experienced laws more cruel than arms, snatched up their weapons under the leadership of Armenius. |

| 33 |

| quum interim tanta erat Varo pacis fiducia, ut ne prodita quidem per Segestem unum principum conjuratione commoveretur. |

Meanwhile Varus was so confident of peace that he was quite unperturbed even when the conspiracy was betrayed to him by Segestes, one of the chiefs. |

| 34 |

| Itaque improvidum et nihil tale metuentem ex improviso adorti, quum ille — ¡o securitas! — ad tribunal citaret, undique invadunt; castra rapiuntur, tres legiones opprimuntur. |

And so when he was unprepared and had no fear of any such thing, at a moment when — what carelessness! — he was actually summoning them to appear before his tribunal, they rose and attacked him from all sides. His camp was seized, and three legions were overwhelmed. |

| 35 |

| Varus perditas res eodem quo Cannensem diem Paulus et fato est et animo secutus. |

Varus met disaster by the same fate and with the same courage as Paulus on the fatal day of Cannæ. |

| 36 |

| Nihil illa cæde per paludes perque silvas cruentius, nihil insultatione barbarorum intolerabilius, præcipue tamen in causarum patronos. |

Never was there slaughter more cruel than took place there in the marshes and woods, never were more intolerable insults inflicted by barbarians, especially those directed against the defense attorneys. |

| 37 |

| Aliis oculos, aliis manus amputabant, uni os obsutum, recisa prius lingua, quam in manu tenens barbarus “tandem” ait “vipera sibilare desisti.” |

They put out the eyes of some of them and cut off the hands of others; they sewed up the mouth of one of them after first cutting out his tongue, exclaiming, “At last, you viper, you have ceased to hiss.” |

| 38 |

| Ipsius quoque consulis corpus, quod militum pietas humi abdiderat, effossum. Signa et aquilas duas adhuc barbari possident, tertiam signifer, priusquam in manus hostium veniret, evulsit mersamque intra baltei sui latebras gerens in cruenta palude sic latuit. Hac clade factum, ut imperium, quod in litore Oceani non steterat, |

The body too of the consul himself, which the dutiful affection of the soldiers had buried, was disinterred. As for the standards and eagles, the barbarians possess two to this day; the third eagle was wrenched from its pole, before it could fall into the hands of the enemy, by the standard-bearer, who, carrying it concealed in the folds round his belt, secreted himself in the blood-stained marsh. The result of this disaster was that the empire, which had not stopped on the shores of the Ocean, |

| 39 |

| in ripa Rheni fluminis staret. |

was checked on the banks of the Rhine. |

|

Cassius Dio Coccejanus, ca. A.D. 150 — 235

History of Rome (written in Greek), 18,1—24,6 |

| |

| Book LVI |

| Chapter 18 |

| 1 |

| His senatusconsultis recens factis, adversus e Germania allatus nuntius triumphos eorum impediit. Nam eodem tempore in Germania hæc quæ nunc dicam acciderunt. Loca ejus quædam Romani tenebant, non vicina invicem, sed ut forte subacta fuerant, sparsa: quam ob causam nec in historiis ulla fit eorum mentio. |

Scarcely had these decrees been passed, when terrible news that arrived from the province of Germany prevented them from holding the festival. I shall now relate the events which had taken place in Germany during this period. The Romans were holding portions of it — not entire regions, but merely such districts as happened to have been subdued, so that no record has been made of the fact — |

| 2 |

| Eis in locis hiberna Romani milites habebant, colonias condebant; mores eorum jam barbari accipere, ad nundinas statas convenire, congressusque cum eis pacatos habere. Neque tamen patriarum consuetudinum‚ morum innatorum, libertatis, armorumque potentiæ obliti penitus fuerant. |

and soldiers of theirs were wintering there and cities were being founded. The barbarians were adapting themselves to Roman ways, were becoming accustomed to hold markets, and were meeting in peaceful assemblages. They had not, however, forgotten their ancestral habits, their native manners, their old life of independence, or the power derived from arms. |

| 3 |

| Itaque dum paulatim, et pedetemtim quodammodo, cautione adhibita, ea dediscerent; mutationem vitæ suæ adeo non gravate ferebant, ut eam ne sentirent qui dem. Ubi vero Quintilius Varus, Germaniæ post administratam Syriam præfectus, rebus ibi gubernandis susceptìs, instituit eam gentem subito simulque transformare, et cum cetera ipsis tanquam servituti subjectis imperare, tum pecunias ut a subditis exigere: |

Hence, so long as they were unlearning these customs gradually and by the way, as one may say, under careful watching, they were not disturbed by the change in their manner of life, and were becoming different without knowing it. But when Quintilius Varus became governor of the province of Germany, and in the discharge of his official duties was administering the affairs of these peoples also, he strove to change them more rapidly. Besides issuing orders to them as if they were actually slaves of the Romans, he exacted money as he would from subject nations. |

| 4 |

| Germani ejus inceptum non tulerunt, primoribus ipsorum amissum principatum desiderantibus, vulgo consuetam rerum rationem peregrinæ dominationi anteferente. Quia autem Romanos multos apud Rhenum, multos apud se versari videntes, rebellionem palam temptare non audebant, |

To this they were in no mood to submit, for the leaders longed for their former ascendancy and the masses preferred their accustomed condition to foreign domination. Now they did not openly revolt, since they saw that there were many Roman troops near the Rhine and many within their own borders; |

| 5 |

| Varum ita acceperunt, ut omnibus ejus jussis obtemperaturi viderentur, proculque eum a Rheno in Cheruscorum fines et ad flumen Visurgim abduxerunt. Ibi summa in pace ac amicitia erga eum viventes in hanc eum opinionem abduxere, quasi possent absque militum opera in servitute contineri. |

instead, they received Varus, pretending that they would do all he demanded of them, and thus they drew him far away from the Rhine into the land of the Cherusci, toward the Weser, and there by behaving in a most peaceful and friendly manner led him to believe that they would live submissively without the presence of soldiers. |

| Chapter 19 |

| 1 |

| Igitur Varus neque milites, quod in hostico fieri debet, uno loco continuit, et multos ex suis hinc inde dedit petentibus infirmioribus, quasi ad præsidia locorum quorundam vel ad comprehendendos latrones vel ad commeatum subvectiones. |

Consequently he did not keep his legions together, as was proper in a hostile country, but distributed many of the soldiers to helpless communities, which asked for them for the alleged purpose of guarding various points, arresting robbers, or escorting provision trains. |

| 2 |

| Erant præcipui inter eos qui conspiraverant, ducesque insidiarum et belli, quod tum conflabatur, Arminius et Sëgimērus, semper cum Varo versati sæpiusque conviventes. |

Among those deepest in the conspiracy and leaders of the plot and of the war were Armenius and Segimerus, who were his constant companions and often shared his mess. |

| 3 |

| Fidente jam rebus Varo, et nihil mali exspectante, ac non modo fidem omnem derogante eis qui rem ut erat suspicati, eum ut sibi caveret monebant ; sed objurgante etiam eos, quod frustra sibi timerent, ac illos calumniarentur. Repente e composito quidam longius remoti Germani insurgunt, |

He accordingly became confident, and expecting no harm, not only refused to believe all those who suspected what was going on and advised him to be on his guard, but actually rebuked them for being needlessly excited and slandering his friends. Then there came an uprising, first on the part of those who lived at a distance from him, deliberately so arranged, |

| 4 |

| nimirum ut contra eos proficiscens Varus, in itinere opportunior cladi esset, quum se per amicorum regionem ire arbitraretur, neve, simul omnibus bellum subito moventibus, sibi caveret. Id consilium eventu comprobatum fuit. Nam et exercitum abducentem deduxerunt, et ipsi, velut auxilia paraturi, ac celeriter subsidio venturi, domi remanserunt. |

in order that Varus should march against them and so be more easily overpowered while proceeding through what was supposed to be friendly country, instead of putting himself on his guard as he would do in case all became hostile to him at once. And so it came to pass. They escorted him as he set out, and then begged to be excused from further attendance, in order, as they claimed, to assemble their allied forces, after which they would quickly come to his aid. |

| 5 |

| Mox acceptis copiis suis quæ jam in promptu certo quodam loco erant, et occisis quos ante ab eo impetratos quisque secum habebat, militibus, in silvis eum jam inviis hærentem assecuti, repente pro subditis hostes se esse ostenderunt, ac mala Romano exercitui multa ac gravia intulerunt. |

Then they took charge of their troops, which were already in waiting somewhere, and after the men in each community had put to death the detachments of soldiers for which they had previously asked, they came upon Varus in the midst of forests by this time almost impenetrable. And there, at the very moment of revealing themselves as enemies instead of subjects, they wrought great and dire havoc. |

| Chapter 20 |

| 1 |

| Erant enim montes convallibus crebris intercepti ac inæquales, arbores autem densæ ac immodicæ proceritatis, quibus Romani etiam ante hostis adventum cædendis viaque patefacienda et pontibus, ubi opus erat, faciundis defatigati fuerant. |

The mountains had an uneven surface broken by ravines, and the trees grew close together and very high. Hence the Romans, even before the enemy assailed them, were having a hard time of it felling trees, building roads, and bridging places that required it. |

| 2 |

| Currus autem et jumenta impedimentis ferendis agebant secum plurima, ut in pace. Sequebantur etiam non pauci pueri ac mulieres calonesque magno numero, qua de causa etiam dissipato agmine iter faciebant. |

They had with them many waggons and many beasts of burden as in time of peace; moreover, not a few women and children and a large retinue of servants were following them — one more reason for their advancing in scattered groups. |

| 3 |

| Interim pluvia cum magno vento superveniens magis adhuc eos dispersit solumque lubricum ad radices et truncos arborum redditum, gressus quam maxime lapsui obnoxios efficiebat, tum arborum summa confracta ac dejecta eos perturbabant. |

Meanwhile a violent rain and wind came up that separated them still further, while the ground, that had become slippery around the roots and logs, made walking very treacherous for them, and the tops of the trees kept breaking off and falling down, causing much confusion. |

| 4 |

| His difficultatibus Romanos tum impeditos Germani undequaque simul per ipsas densissimas silvas, quippe callium periti, subito consectati circumvenere ac initio eminus tantum impetiere, post, quum nemo se defenderet, multi vulnerarentur, comminus congressi sunt. |

While the Romans were in such difficulties, the barbarians suddenly surrounded them on all sides at once, coming through the densest thickets, as they were acquainted with the paths. At first they hurled their volleys from a distance; then, as no one defended himself and many were wounded, they approached closer to them. |

| 5 |

| Nempe nullo ordine, promiscuo agmine inter currus et inermes proficiscentes Romani neque coire inter se facile poterant ac pauciores ubique a pluribus quum invaderentur, multa incommoda passi sunt, reddiderunt nullum; |

For the Romans were not proceeding in any regular order, but were mixed in helter-skelter with the waggons and the unarmed, and so, being unable to form readily anywhere in a body, and being fewer at every point than their assailants, they suffered greatly and could offer no resistance at all. |

| Chapter 21 |

| 1 |

| Quare locum ibi ut in monte silvis obsito opportunum nacti castra fecerunt ; hinc majori curruum et quibus carere possent impedimentorum parte combusta aut relicta, magis composito agmine potridie progressi sunt in locum nemore vacuum, neque hoc quidem sine suorum cæde. |

Accordingly they encamped on the spot, after securing a suitable place, so far as that was possible on a wooded mountain; and afterwards they either burned or abandoned most of their waggons and everything else that was not absolutely necessary to them. The next day they advanced in a little better order, and even reached open country, though they did not get off without loss. |

| 2 |

| Inde profecti iterum in silvas inciderunt et quum ab invadentibus hostibus se conarentur defendere, haud parum id ipsum ad cladem contulit. Nam in arctum contracto exercitu ut confertim equites simul peditesque in hostem incurrerent, multa sibi invicem ipsi damna dederunt, multa ab arboribus passi sunt. |

Upon setting out from there they plunged into the woods again, where they defended themselves against their assailants, but suffered their heaviest losses while doing so. For since they had to form their lines in a narrow space, in order that the cavalry and infantry together might run down the enemy, they collided frequently with one another and with the trees. |

| 3 |

| Illuxerat jam dies ipsique in itinere versabantur, quum rursum effusus imber ventusque vehemens eos adortus est, sic ut neque procedere neque consistere firmitr possent, quin et usus armorum ipsis ademptus est ut neque sagittas neque pila neque scuta, quippe madentia, commode tractare possent. |

They were still advancing when the fourth day dawned, and again a heavy downpour and violent wind assailed them, preventing them from going forward and even from standing securely, and moreover depriving them of the use of their weapons. For they could not handle their bows or their javelins with any success, nor, for that matter, their shields, which were thoroughly soaked. |

| 4 |

| Ea hosti, quod plurique levis erant armaturæ ac aggredi regredique tuto poterant, minus eveniebant. Jam et numero aucti Germani erant, quum permulti ante ambigui, nunc vel prædæ causa se eis adjungerent. Quo facilius Romanos, qui multos jam prioribus cladibus suorum amiserant, et circumdabant et trucidabant. |

Their opponents, on the other hand, being for the most part lightly equipped, and able to approach and retire freely, suffered less from the storm. Furthermore, the enemy's forces had greatly increased, as many of those who had at first wavered joined them, largely in the hope of plunder, and thus they could more easily encircle and strike down the Romans, whose ranks were now thinned, many having perished in the earlier fighting. |

| 5 |

| Ideo Varus aliique primores, acceptis jam vulneribus, quum metuerent ne vel in hostium potestatem vivi venirent vel ab infensissimo hoste interficerentur, sibi manus ipsi attulerunt, rem duram quidem, necessariam tamen ausi. |

Varus, therefore, and all the more prominent officers, fearing that they should either be captured alive or be killed by their bitterest foes (for they had already been wounded), made bold to do a thing that was terrible yet unavoidable: they took their own lives. |

| Chapter 22 |

| 1 |

| Horum audita morte, nemo jam etiam eorum quibus robur suppetebat, se defendit, sed alii ducis sui exemplum imitati sunt, alii armis abjectis cædere volentibus se præbuerunt. Nam fugere quidem, etiamsi maxime vellet, nemo poterat. |

When news of this had spread, none of the rest, even if he had any strength left, defended himself any longer. Some imitated their leader, and others, casting aside their arms, allowed anybody who pleased to slay them; for to flee was impossible, however much one might desire to do so. |

| 2 |

| Itaque jam nullo impediente metu viri omnes equique cædebantur. |

Every man, therefore, and every horse was cut down without fear of resistance, and the . . . |

| 2a |

| Et munitis locis omnibus uno excepto barbari potiti sunt. Ad quod dum adhærescunt, neque Rhenum trjecerant neque in Galliam impressionem fecerunt. Sed neque castellum illud potuerant expugnare, quod ipsi oppugnandi rationem nescirent, Romani autem magnam vim sagittariorum haberent, a quibus repellebantur et plurimi occidebantur. |

2a And the barbarians occupied all the strongholds save one, their delay at which prevented them from either crossing the Rhine or invading Gaul. Yet they found themselves unable to reduce this fort, because they did not understand the conduct of sieges, and because the Romans employed numerous archers, who repeatedly repulsed them and destroyed large numbers of them. |

| 2b |

| Deinde quum Rhenum præsidiis tueri a Romanis et Tiberium cum magnis copiis adventare audiissent, plerique a castello recesserunt ; reliqui ne subitis obsessorum excursionibus infestarentur, longius digressi vias occuparunt, sperantes penuria commeatus eos expugnatum iri. Obsessi, dum suppetebant cibaria, auxilium exspectantes loco se continuerunt. Sed quum nemo opem ferret et fame urgerentur, tempestuosa nocte observata egressi (erant autem pauci milites, multi inermes), |

2b Later they learned that the Romans had posted a guard at the Rhine, and that Tiberius was approaching with an imposing army. Therefore most of the barbarians retired from the fort, and even the detachment still left there withdrew to a considerable distance, so as not to be injured by sudden sallies on the part of the garrison, and then kept watch of the roads, hoping to capture the garrison through the failure of their provisions. The Romans inside, so long as they had plenty of food, remained where they were, awaiting relief; but when no one came to their assistance and they were also hard pressed by hunger, they waited merely for a stormy night and then stole forth. Now the soldiers were but few, the unarmed many. |

| 2c |

| primam quidem excubiarum stationem secundamque prætereuntes, ad tertiam vero advenientes, mulieribus puerisque ex ærumnis ac timore et propter tenebras frigusque interpellantibus armatos deprehensi sunt, |

They succeeded in getting past the foe’s first and second outposts, but when they reached the third, they were discovered, for the women and children, by reason of their fatigue and fear as well as on account of the darkness and cold, kept calling to the warriors to come back. |

| 3 |

| omnesque Romani ea die internecione deleti aut capti fuissent, ni Germani diripienda præda occupari cœpissent. Sic enim factum est ut robustissimus quisque aufugeret, ac tubicines, qui cum eis erant, signum cursus concinentes opinionem hostibus injecerunt adesse missa ab Asprenate auxilia. |

And they would all have perished or been captured, had the barbarians not been occupied in seizing the plunder. This afforded an opportunity for the most hardy to get some distance away, and the trumpeters with them by sounding the signal for a double-quick march caused the enemy to think that they had been sent by Asprenas. |

| 4 |

| Jam enim nox supervenerat ut cerni non possent. Ea res inhibuit ab insequendo Germanos. Et Asprenas, cognita re, vere auxilium suis tulit. Postea temporis nonnulli quoque captorum domum redierunt, redempti a necessariis, quibus id concessum ea condicione, ut illi extra Italìam manerent. |

Therefore the foe ceased his pursuit, and Asprenas, upon learning what was taking place, actually did render them assistance. Some of the prisoners were afterwards ransomed by their relatives and returned from captivity; for this was permitted on condition that the men ransomed should remain outside of Italy. This, however, occurred later. |

| Chapter 23 |

| 1 |

| Augustus, Variana clade audita, vestem, ut quidam memorant, laceravit inque magno luctu fuit propter amissum exercitum metumque de Germanis Galliisque, maxime quod eas gentes jam ipsam Italiam ac Romam petituras verebatur, ac neque civium Romanorum juventus magni momenti supererat et sociorum auxilia, quæ alicujus essent pretii, afflicta erant. |

Augustus, when he learned of the disaster to Varus, rent his garments, as some report, and mourned greatly, not only because of the soldiers who had been lost, but also because of his fear for the German and Gallic provinces, and particularly because he expected that the enemy would march against Italy and against Rome itself. For there were no citizens of military age left worth mentioning, and the allied forces that were of any value had suffered severely. |

| 2 |

| Nihilominus, tamen ad omnia se, quantum præsens rerum condicio ferebat, comparavit. Et quoniam ii qui militari essent ætate dare nomina nolebant, ex eis qui nondum annum quintum et trigesimum attigissent, quintum quemque, e natu majoribus decimum quemque, ut sors in quemvis incidisset, bonis privatum infamia notavit. |

Nevertheless, he made preparations as best he could in view of the circumstances; and when no men of military age showed a willingness to be enrolled, he made them draw lots, depriving of his property and disfranchising every fifth man of those still under thirty-five and every tenth man among those who had passed that age. |

| 3 |

| Postremo, quum multi ne sic quidem obœdirent, quosdam morte mulctavit. Igitur collecta, quantam maximam potuit, e veteranis et libertis per sortem multitudine, eam manum statim Tiberio celeriter in Germaniam ducendam dedit. |

Finally, as a great many paid no heed to him even then, he put some to death. He chose by lot as many as he could of those who had already completed their term of service and of the freedmen, and after enrolling them sent them in haste with Tiberius into the province of Germany. |

| 4 |

| Et quia complures Galli ac Germani Romæ versabantur, partim alia de causa peregre agentes, partim inter prætorianos militantes, veritus ne quid novi molirentur, hos quidem in insulas quasdam amandavit, illos inermes urbe exire jussit. |

And as there were in Rome a large number of Gauls and Germans, some of them serving in the pretorian guard and others sojourning there for various reasons, he feared they might begin a rebellion; hence he sent away such as were in his bodyguard to certain islands and ordered those who were unarmed to leave the city. |

| Chapter 24 |

| 1 |

| Hæc tum ab Augusto acta, nec e more vel cetera vel ipsi ludi celebrati. Secundum hæc, ubi accepit nonnullos milites superfuisse cladi, Germanias præsidio contineri, hostem ne ad Rhenum quidem accedere ausum, terrore liberatus rem in deliberationem vocavit. |

This was the way he handled matters at that time; and none of the usual business was carried on nor were the festivals celebrated. Later, when he heard that some of the soldiers had been saved, that the Germanies were garrisoned, and that the enemy did not venture to come even to the Rhine, he ceased to be alarmed and paused to consider the matter. |

| 2 |

| Videbatur enim ei hoc tantum ac multiplex malum non sine divina quadam ira accidisse suspectamque deûm voluntatem præterea, propter prodigia quæ ante ac post eam cladem evenerant, magnopere habebat. |

For a catastrophe so great and sudden as this, it seemed to him, could have been due to nothing else than the wrath of some divinity; moreover, by reason of the portents which occurred both before the defeat and afterwards, he was strongly inclined to suspect some superhuman agency. |

| 3 |

| Etenim templum Martis in campo Martio fulmine tactum fuerat et locustæ multæ in ipsam urbem devolantes ab hirundinibus consumptæ ; Alpium vertices in se invicem corruere, tresque columnas igneas emisisse visi. Cælum sæpius ardentis præbuerat speciem ; |

For the temple of Mars in the field of the same name was struck by lightning, and many locusts flew into the very city and were devoured by swallows; the peaks of the Alps seemed to collapse upon one another and to send up three columns of fire; the sky in many places seemed ablaze |

| 4 |

| multi simul cometæ effulserant. Hastæ a septentrione latæ in Romanorum castra decidere existimatæ ; circa aras eorum apes favos finxerant. Quædam Victoriæ statua in Germania ad hostium regionem spectans ad Italiam obversa ; |

and numerous comets appeared at one and the same time; spears seemed to dart from the north and to fall in the direction of the Roman camps; bees formed their combs about the altars in the camps; a statue of Victory that was in the province of Germany and faced the enemy's territory turned about to face Italy; |

| 5 |

| etiam aliquando circa aquilas in exercitu inane militum certamen fuit, quasi barbari irrupissent. |

and in one instance there was a futile battle and conflict of the soldiers over the eagles in the camps, the soldiers believing that the barbarians had fallen upon them.

For these reasons, then, and also because . . .

|

| Chapter 25 |

| 1 |

| Anno sequenti … Marco Æmilio Lepido et Statilio Tauro consulibus [11 p. Chr n.], Tiberius [Rhenum sibi transeundem non censuit, sed, quiete se continuit observans, an id barbari facturi essent. Verum nec illi, præsentia ejus cognita, transire ausi fuerant. |

In the following year … in the consulship of Marcus Æmilius Lepidus and Statilius Taurus, Tiberius did not see fit to cross the Rhine, but kept quiet, watching to see that the barbarians did not cross. And they, knowing him to be there, did not venture to cross in their turn. |

| 2 |

| Post quæ ipse] et Germanicus, cui proconsulare erat imperium, impressionem in Germaniam fecerunt ac populati nonnullas ejus partes. Nullo tamen prœlio hostem vicerunt, quum nemo manum consereret, neque ullum populum subegerunt, |

After this, he himself and Germanicus, the latter as proconsul, invaded Germany and laid waste to some parts of it. But since no one joined battle with them, they won no victories over the enemy and subjugated no tribes. |

| 3 |

| veriti enim, ne rursus cladem acciperent, haud ita procul a Rheno discesserunt, sed prope eum usque ad autumnum morati, ludis in honorem natalium Augusti actis ac ministerio centurionum edito equesteri certamine, in Italiam reversi sunt. |

For, being afraid of suffering another disaster, they did not venture far from the Rhine, but stayed close to it until autumn and, after celebrating games in honor of Augustus’ birthday and staging a horse race administered by the centurions, they returned to Italy. |